1. Challenges ahead

Human rights are contested. This comes as no surprise because they always have been. In recent years, however, new forms of criticism have emerged that merit close attention because of at least four reasons: First, these (often radical) criticisms may be justified and thus provide insights and a better guide to action than other views of human rights that have perhaps petrified into dead orthodoxies. Second, the battery of recent criticism may undermine the project of human rights even if such criticism rests on shaky grounds. Without a convincing human rights idea, why pursue the human rights project? Third, we live in dire times in which the very thought of human life being protected by the equal rights of everyone has come under sustained fire from old foes and new forms of ethnonationalist authoritarianism, with or without a democratic facade, but always with an antiegalitarian core operating against basic liberties. Fourth, such fundamental challenges as war, poverty or climate change seem to demand that we reimage human rights. Therefore, deep engagement with the theory of human rights is more than an intellectual pastime – it has a profound political point if one aims to protect the exiting limited spheres of a lifeworld of decency.

2. Beyond the conventional: Broadening the perspective of human rights theory

If one wishes to travel down this road, one has to consider the history, normative justification and psychological foundations of human rights. Why include these different topics in the inquiry? The reason is that given the state of current reflection one cannot attempt to talk about the justification of human rights without having understood what their history teaches us about their origins and development. Moreover, there is a long tradition of thought about the psychological foundations of ethical ideas and there exist very fertile empirical inquiries into the nature and origins of normative concepts in fields ranging from child psychology and behavioral economics to cognitive neuroscience. Any account of human rights that intends to meet the theoretical challenges ahead therefore must investigate whether an empirically based theory of mind tells us something interesting about human rights, not least whether there are reasons drawn from recent research to debunk this idea, as influential voices argue. These kinds of considerations have not reached the main currents of human rights theory, which is unfortunate.

3. Concept and history

The argument laid out in Mind and Rights first clarifies the concept of rights using the tools of analytical moral and legal theory.

Second, it turns to a major battleground of current human rights debates: human rights history. The history of human rights is not just the history of the explicit idea, nor does it simply track the history of the terms we now use to express this idea. To look for a Universal Declaration in cuneiform is a hopeless task. The historical account must be much more differentiated and must consider, importantly, normative ideas that are not human rights but that formed the building blocks of the slow development of the idea. These include basic moral judgments about the claims human beings have. Key to such perceptions are not only explicit moral rules or legal codes but also social practices, not least the struggles of human beings through the ages for what they thought to be their due.

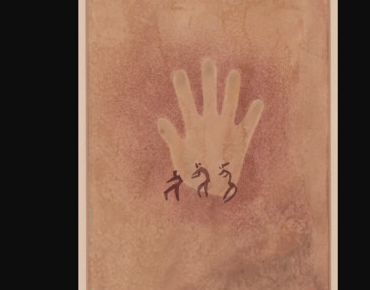

This widens the perspective of human rights history considerably. Crucially, it provides methodological tools that help us to start inquiring about a somewhat neglected part of human rights history: the role such judgments played in the lives and societies of indigenous peoples. It is important to ask how these peoples who suffered for a long time under mostly European powers perceived their conquest, repression, exploitation and enslavement. The Hereros, for example, who were driven by German colonial forces into the desert to die – were they just experiencing the physical pain of their situation or also the injustice of their suffering and, in whatever conceptual scheme, the violations of claims that they thought they had? Such moral experience – albeit not couched in modern human rights terms – is very important for a history of this idea that aims to avoid embarrassing ethnocentric blind spots.

The result of the historical inquiry is that the normative raw material for constructing human rights can be found in very different ages and cultures. They are no prerogative of what is sometimes called “Western” culture. These building blocks were turned through a long, twisted and discontinuous process into the historically recently developed explicit idea of human rights as an ethical, political and ultimately legal concept. This history – in particular the course of the establishment of the concrete legal human rights regime as we have known it since 1945, built on the mutually supporting pillars of constitutions and regional and international systems of rights protection – confirms that key to understanding the normative core of human rights are not vaguely circumscribed, often essentialist cultural notions but specific, normative, deeply political positions formed by autonomously reflecting human agents as to the status and justified claims of human beings and their fundamental duties. It is a mistake to depoliticize the intrinsically political project of human rights.

4. Human rights: Ideological litter from the past?

The next step is to investigate what grounds there are for the normative justification of human rights. The current theoretical discourse on this topic is rich and controversial. The engagement with these theories seems to confirm that a justificatory theory of human rights needs to include three elements: first, an anthropological element that helps to motivate the selection of human goods that human rights protect, which are shaped by history but not entirely contingent upon it; second, a theory of the political preconditions for the enjoyment of these goods; and, third, rich normative principles of egalitarian justice, substantive obligatory solidarity and the intrinsic worth of human beings that provide the normative reasons to entitle humans to some goods and obligate others to shoulder the sometimes light, sometimes heavy burdens that these entitlements entail.

One point merits highlighting: The political theory of human rights needs to be based on the central lessons to be learned from the analysis of the content, political institutions and practices of the ideologies that led to the atrocious bloodshed of the last century, in particular National Socialism, which expressed through concentrations camps and gas chambers its contempt for human beings. As Vasily Grossman remarked in one of the first eyewitness accounts of what had been going on in the concentration camps: “We must remember that Fascism and racism will emerge from this war not only with the bitterness of defeat but also with sweet memories of the ease with which it is possible to commit mass murder.” This experience established beyond doubt the need to protect robustly the basic claims of human beings, irrespective of what other political aims one might pursue.

5. The last piece in the puzzle

The last step is to engage seriously with current moral psychology, evolutionary theory and cognitive science. Very robust assertions have been offered as to the nature and origins of human moral concepts, including human rights. These include the claim that we humans possess cognitive structures that do not enable us to gain genuine insights, instead leading us systematically astray. Our cognitive machinery fools us into believing in certain moral concepts – including human rights – that are nothing but cognitive illusions. Some voices in the field of cognitive neuroscience are thus conjuring up yet again the malign demon that makes us believe that something is true which is in fact false, the same demon that haunted Descartes’ epistemological thought. This malign demon resides within us, in the hardwired cognitive structures that appear falsely to us as key to ethical insight.

What the critical discussion of such claims, the assessment of what a sufficiently complex theory of the evolutionary development of moral cognition and the review of current moral psychology, in particular child psychology, teach us about the structures and origins of moral thought, emotion and motivation leads to different conclusions: There is no reason whatsoever derivable from the theories of evolution and human psychology that undermines the case for human rights. On the contrary, there are promising theoretical approaches – in particular a mentalist account of human moral cognition – that buttress the perception that the deep structure of human moral psychology in important respects supports the human rights project and is not its hidden foe. There is no inborn charter of human rights, but there are structures of moral cognition that make the complex process of developing human rights possible. This is a significant result. One cannot draw any normative conclusions from psychological facts. But it is important, given its often fascinating and illuminating results, to do justice to this research and to clarify what it truly implies for normative questions of such importance as human rights.

6. A simple point

Human rights would make no sense if all members of the bewildering and potentially ultimately self-destructive human species were not equally worth the effort of guaranteeing with the means of rights in ethics, politics and law their capabilities to pursue their particular vision of life. After everything has been said and done, therefore, human rights make a simple point: They embody an assertion of the worth of every human’s life, with all its folly, desperation, missed opportunities, occasional insights and fragile and rare moments of bliss, and the spark of greatness that is at its core. Its history, deep justification and what we know about human moral cognition provide every reason to continue to keep the idea of human rights alive, not least by criticizing the shortcomings of their legal and political practice, by exposing their abuse and by identifying their blind spots, but also by reasserting the grounds of their profound appeal.

Latest Comments

Have your say!