With the right light shone upon them, small objects cast large shadows. So it is with the American Short Story, a genre whose outsized presence in American literature – where it is a common feature of university curricula – and capacity to incorporate diverse voices and experiences, often belies its necessary brevity and neglect by a book-buying public. The tension between these scales produces a trompe l’oeil so confusing that critics of the short story are not really sure what to do with it. In short, the “short story” suffers in a contemporary literary study that has overtly embraced the novel as the proper form of prose fiction, following Route 1 to the Great American Novel not the byroads to the quirky sideshow of the Great American Story. At once a genre known popularly as one of American literature’s key contributions to world literature and the style that frequently permits entry to key publishing and institutional venues such as the Iowa Writer’s Workshop or The New Yorker Magazine that might launch an author’s ambitions, it is also one upon which it is almost impossible to build a successful career, given sales figures of short story collections comparative to the novel. Its foundations may be deep, but they are narrow. The short story tries audaciously to be liked to the point of protesting a little too much. Glittering prizes must be established to support it where audiences will not. University creative writing programs must house it on campus so that it doesn’t hurt itself out in the real world. Trying to become a writer based on the short story alone is like setting off on stilts; we look up impressed at the sheer skill and moxie, but only because it is all too precarious, careening – a bit gauche. Short story writing can seem like the kind of work performed by a talented, loveable clown who chose wholly the wrong field of endeavour and ended up on life support.

The awkwardness of its status and performance poses many questions. First, do we have this all topsy turvy? As an unfortunate result of its name in English the form exists as something lesser than The Novel. Yet, the “short story” in the New World has earlier origins than long-form fiction. So, in fairness, should The Novel properly be called “The Long Story” (in fact, Hawthorne used this term for his short novel, The Scarlet Letter)leaving “short fiction” to lay claim to the safer ground of being “Story,” and the novel to be perceived as slightly tedious and long-winded? “Short Story” seems like it carries within it a self-criticism, or self-loathing; an implication that its best writers can set off fireworks but cannot go the distance. Yet, as Gavin Jones and I have shown in The Cambridge Companion to the American Short Story, a long-running and rather nauseating ontological colloquy about what the short story is (especially relative to the novel or poetry), has often directed our attention away from what it does, which reveals much about the marketplace, American attitudes to art and culture, and how race and ethnicity play out in American literary history within the interstitial spaces that are really where quite a lot of what is truly interesting actually happens. At a formal level the short story engages in critique of cultural norms, tests their limits, even as it dazzles with its spectacles and pleasures. Rather than seeing the short story as a weirdly uncertain, negatively-defined, non-form (not-poetry, not-drama, not-novel) in the cultural field, what happens when we see it as the centre of a network of relations; swinging on a trapeze so as to expose the very flimsiness not just of a writer’s life and career but of our dominant categories? As we argue in the Introduction to the collection, perhaps the rapid approach of the short story’s ending, the hovering pendulum of time that marks it out as distinct from a novel or poem that can be precisely as long as it wants to be, can rub a whole culture up the wrong way. And is this especially true in an American culture that seems so unwilling to accept that all things – forms of literature and political systems among them – are always-already marked for death?

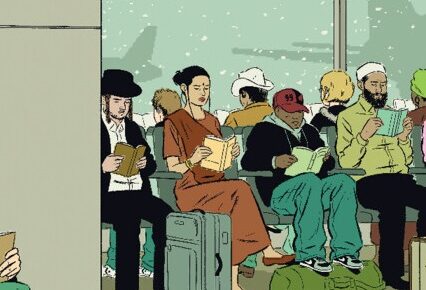

Taking a different angle that navigates between an exploded view of the literary field and close readings of the localised, frequently brilliant performances for which the form is notable, this collection seeks to renovate study of the American short story. It traces its origins back to Western settlement and before to show that a Big Country has not always needed a Big Form to describe it. Perhaps, as we think anew about precarity, climate change, democratic crises of various sorts, and the diminished status of the U.S. on the world scene, we need to reset our lens to focus on forms that were always precarious, slight-in-some-way, and that reified time’s passage and uncertain futures. The Cambridge Companion to the American Short Story asks what American literature looks like when we trace the lines of motion and flight of a form especially given to migrancy – being published simultaneously in multiple locations, never contained wholly by the codex book – rather than emphasise the codification and finality of the officially-published novel. The effects are surprising, rich and marked by a flexibility, dynamism and acrobatic pizzazz that is seldom fully captured by our existing purview.

Latest Comments

Have your say!