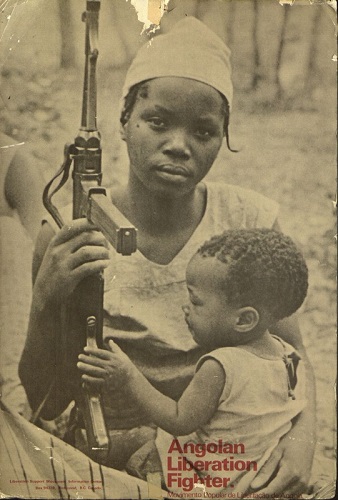

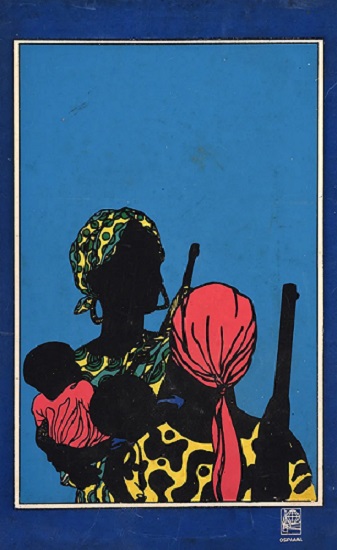

A woman holding a baby in one arm with a gun slung over the other. It’s a powerful image of a society mobilizing for revolution, carrying overtones of self-determination and gender equality. Striking in its individuality, the image is likely familiar to many across the globe since versions appeared in the late 1960s and 1970s in the United States, Cuba, Vietnam, Mozambique, and elsewhere.

This image, and the intellectual networks that ferried it across the globe, lie at the heart of the Tricontinental Revolution: Third World Radicalism and the Cold War, recently released by Cambridge University Press. Some readers might be familiar with the idea of Tricontinentalism as part of Cuban foreign policy, but the wide circulation of the woman-baby-gun image offers visual evidence that solidarity among revolutionaries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America was a truly global idea.

The volume argues that Tricontinentalism best captures the secular, militant, and leftist anti-imperialism that won adherents across the Global South in the 1960s and 1970s. Revolutionaries on three continents – along with their diasporic communities and allies in Europe and the United States – articulated shared critiques of Western dominance and envisioned new self-determining, socialist societies. This radical Third Worldism directly challenged the American-led international system by informing everything from local revolts to the attempted creation of a New International Economic Order.

The woman-baby-gun image provides a colorful example of the circulation and deployment of Tricontinental ideas. Designed by Black Panther artist Emory Douglas in 1967 to capture elements of continental African revolutions, the Cuban artist Lazaro Abreu adapted it as a poster for Tricontinental magazine. The publication was a clearinghouse for interviews of and writings about the world’s leading revolutionaries. The Cuban government distributed Tricontinental globally with vibrant posters folded inside, encouraging a shared iconography based on the ideas discussed in its pages.

Deploying the woman-child-gun trope allowed groups to communicate a set of values while claiming membership in this global movement. North Vietnam produced its own version while the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) posed photographs to mirror it. The image came full circle when an adaptation adorned the posters of U.S. activists criticizing their government’s intervention against the Soviet-backed Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in 1976, uniting a multiracial coalition behind imagery associated with the Black Power Movement.

The iconography’s journey reveals that Tricontinentalism involved the collaboration of state and non-state actors. The combination of transnational membership and radical worldview makes it distinct from other iterations of Third Worldism, notably the state-based multilateralism articulated at Bandung a decade prior. Yet scholars have just begun to recognize these distinctions.

The Tricontinental Revolution overcomes regional and linguistic barriers by uniting twelve experts on individual national movements. Taken together, the essays identify key elements of Tricontinentalism, while situating it within the complex, sometimes competing visions that drove the search for anti-imperial solidarity during the 20th century.

Tricontinentalism argued that unity across three continents was necessary to confront the global power of the United States, which supplanted European imperialism during the Cold War. A leftist vision of egalitarian revolution took inspiration from the Soviet model but adapted it to local circumstances, prioritizing the struggle against imperialism over class warfare and shifting the mantle of leadership to the Global South. Connections with likeminded Third World revolutionaries sometimes provided concrete material assistance, but more often they helped legitimize individual revolutionary groups.

These ideas informed a powerful movement that defined the 1960s and 1970s as decades of global revolution. These concepts – and the iconography that communicated them – continue to influence global visions of resistance, positioning Tricontinentalism as an important window into the broader phenomena of anti-imperial solidarity and Southern revolution.

Latest Comments

Have your say!