Section V of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, titled “A City Visible but Unseen,” is not about an imaginary city but a migrant ghetto wilfully disavowed. The unseen citizenry are undocumented migrants in London who, because of the Thatcher government’s austerity cuts, cannot find affordable accommodation in the public or private sectors, and who live in the Shandaar café for a pittance. When the café is engulfed in flames later in the novel, Rushdie describes these forsaken lives as “faceless persons [who] stand at windows waving piteously for help, being unable to scream.”

Sigmund Freud’s idea of the uncanny, where the dis-identity of the home and the unhomely sustains each category, can be applied to the infrastructure of unequal cities. The slum, “an informal space outside of, but tightly intertwined with, governance institutions and property markets,” as Lisa Weinstein states, lends itself to the definitional anxiety constitutive of the uncanny. It is familiar yet alienating, visible but unseen. Danny Boyle’s hit movie Slumdog Millionaire (2008) coined the term ‘slumdog’ to describe feral strays who prowl the slums, including children, drug dealers, hustlers, warlords. The narrative is a bildungsroman, the accidental triumph of the mobility hero conditional upon his escaping the slum. The slum adversities themselves remain unchanged and unchallenged.

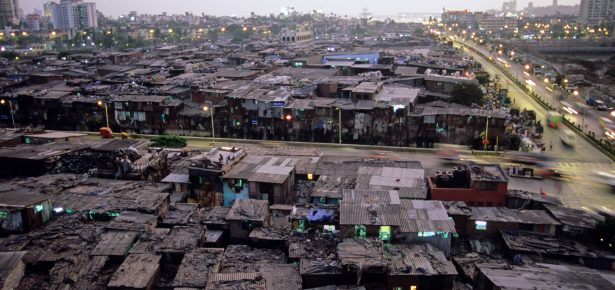

Slumdog Millionaire cannot see the individual in the collective enmired in endemic poverty. The location of Slumdog Millionaire is Dharavi but different slum sensoriums are greedily collapsed into one in the depiction. Claustrophobic density, shit, standing water, riots, garbage hills, bulldozers. Urban studies scholars have argued that Dharavi is probably safer than most American cities: Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava called it a “user-generated city,” its 80 neighbourhoods developed organically and incrementally by generations of residents. There were demonstrations in Dharavi about the title of Slumdog Millionaire: the word ‘slum’ had caused outrage, not the word ‘dog.’

In my book, Unseen City, I explore the possibility of a more proximate and intimate engagement with the psychic lives of the urban poor. I discuss a crop of twenty-first-century non-fiction in this context: Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers; Siddhartha Deb’s The Beautiful and the Damned; Sonia Faleiro’s Beautiful Thing. Boo uses sparse and terse language while narrative details abound, making the reader do the interpretive work of piecing together motive, intention, meaning. With overworked boys sorting trash all day, language is transactional: Boo makes them speak by an almost mechanical transcription of voice and her approximation of thoughts (based on sustained conversations and fact-checking interviews). She shows us people who dream not only of survival but full civic participation. The slum space is not negative – Boo details how migrants reclaim solid land from a bog and how garbage traders (“broken-toothed, profit-minded Santas”) sell the trash of Mumbai’s rich to recycling plants. The works by Faleiro, Deb, and Boo have ‘beautiful’ in the title. Despite the tragic undertone of the stories, what stays with the reader is the resistance and resourcefulness of the characters, painstakingly building up what is systematically razed to the ground.

Latest Comments

Have your say!