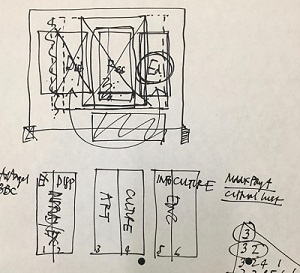

Researching the book Economics of Visual Art, I came across a drawing in the Tate Archives. It is a “concept sketch” for Tate Modern. It was drawn in 1991 — a full nine years before the building opened, and still a few years before Bankside Power Station was chosen as the site. The drawing was made by Nicholas Serota, the longtime director of Tate who retired in 2017. The sketch holds a story of what the arts might have to offer economics — a story about how sometimes value only comes to be known over time, and requires imagination.

The idea of a modern art museum in London was not new when Serota took over the reins of the Tate Gallery in 1988, or when he made the sketch a few years later. He had had the idea of a modern art museum in London since the early 1970s. The art collector and philanthropist Peggy Guggenheim had had this idea in the 1930s. In 1964, the Tate Gallery hosted an exhibition of Guggenheim’s collection of modern art, hoping to court a donation. But the plans were overshadowed by the death of Winston Churchill. As Guggenheim later wrote in her memoir, “My only rival was Churchill’s funeral.” i

By the early 1990s, the Tate had decided it would be impossible to build a museum of modern art on its own site in Pimlico. (The square footage needed would in fact reach across the Thames to the current headquarters of the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6.) The current site of Tate Modern emerged by chance in 1993 when the Tate Deputy Director Francis Carnwath visited Bankside Power Station for a BBC programme on imperiled historic buildings. Carnwath relayed the idea to Serota in passing, and Serota went and paced the building site that night to see if the power station was too large. The museum still went through many planning stages and considered sites, among them Billingsgate Fish Market (project name: Moby Dick). After the ups and downs of successful Lottery funding, but also asbestos discovery and a bankrupted building firm, the museum opened to the public in May 2000.

Tate Modern was an unbridled success, far beyond the imagination of the McKinsey consultants who analyzed the potential economic impact. The museum expected 2 million annual visitors and received 5 million. Tate Modern generated economic value for the surrounding area—in employment numbers, tax receipts, and property values—but the museum did not “own” that value. Those financial gains were a positive externality of the project. In economic terms, they were a market failure. Some economists attempt to model these sorts of civic monuments—and to put quantifiable value onto public goods like the Tate Modern—using methods such as contingent valuation. This method attempts quixotically to quantify the change in one’s happiness if, say, the British Library were closed or the Natural History Museum attended. It is very difficult to define and quantify this value economically. The questionnaires have an existentially poetic impossibility to them:

Take your life as it currently is, but now imagine that you have visited the Natural History Museum [once every [frequency] months (in other words, about [frequency] over the year)] alone or with your family/friends. Assume that you usually spent one to two hours there per visit and vary the activities each time”. Overall how satisfied would you be with your life?ii

It is hard to imagine many people who could precisely and accurately answer that question, though the surveys did relatably confirm that people’s favorite displays at the Natural History Museum are, in rank order: dinosaurs, whales, and volcanoes.iii

Economics offers systems of engineering, of structural support to make an institution like Tate Modern possible. But then art offers the engine of imagination, of sketching a museum as a glimmer of an idea, years before it could be willed into reality.

Left to its own devices economics can lead to a monoculture. These projects demand imagination and risk — and investment — at the moment the outcome is least certain. In those early days, the logic of markets — that price represents value — does not work. Instead, we rely on a kind of artistic work at a managerial scale, bringing things into being that both rely on and defy the structures of markets, creating value far beyond themselves.

i Stephenson, 2018. Guggenheim, Peggy (2005 [1979]). Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict, Andre Deutsch: London 1979, p.369.

ii Bakhshi, et al., pp. 25 and 69.

iii Bakhshi, et al., p. 38.

Latest Comments

Have your say!