Image Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

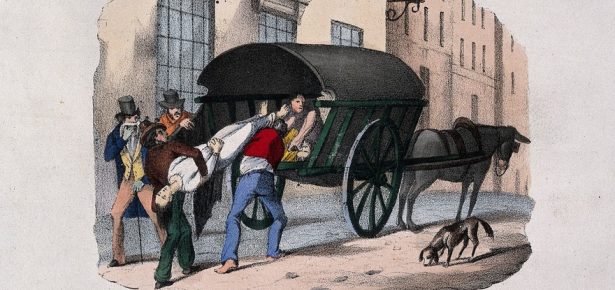

As we all too readily know, a pandemic affects everything, be it social, economic or cultural. Between 1816 and 1923 six global outbreaks of cholera took place. Scientists eventually established that a highly infectious bacillus found in contaminated water caused cholera, rather than breathing in clouds of bad air or “miasma”. L’elisir d’amore was created during the Second Great Cholera Pandemic of 1829-37, when the miasmatic theory still ruled. The disease swept across Europe and North and South America in multiple waves, triggering mass panic, riots, scapegoating of immigrants, and hundreds of thousands of deaths. Cholera killed quickly, often in a matter of hours. People would develop uncontrollable vomiting and diarrhea, their kidneys would fail, and their hearts would give out. Gaetano Donizetti lost his wife to cholera in 1835. This contemporary and widely circulated image captures the horrific nature of the disease and the shock incurred by how rapidly it destroyed life. One of the dramatic markers of cholera was that it turned the skin and mucous membranes a blue color (cyanosis).

The fear of contracting cholera led to the marketing of a number of largely futile preventives and remedies. These are captured in a satirical image from 1832 of a man surrounded by hopeful cures, including bottles of red wine and a tincture of a plant called solanum dulcamara. (See figure 2.)

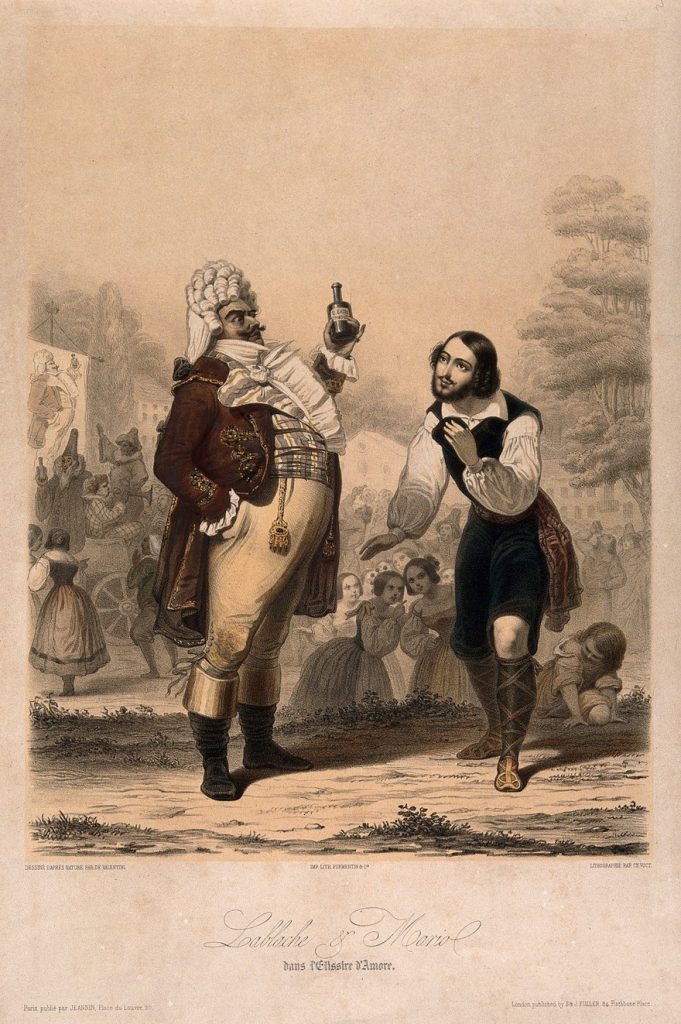

Red wine and dulcamara? In the realm of opera, these names immediately recall Donizetti and Felice Romani’s L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love), which had its premiere on 12 May 1832, at Milan’s Teatro della Conobbiana. The tale of the travelling Dr Dulcamara who sells red wine to the lovelorn Nemorino as a love potion and the plot’s love triangle involving the supposed peasant Nemorino, the wealthy landowner Adina, and the military sergeant Belcore remains popular to the present day. What is often forgotten, though, is that the opera was set and opened amidst a cholera pandemic.

In Italy, France, Russia and Britain cholera riots erupted where the poor (many of whom believed they were being deliberately poisoned by their respective governments) joined with other revolutionary groups such as Mazzanini’s Young Italy to call for an end to corrupt rule and rulers. Belcore, the recruiting sergeant who arrives in the village with his troops, reflects the increase of military surveillance in the aftermath of the 1830 national revolutions to squelch such possible rebellions. He also represents the use of the army at the time to seek out cases of cholera and viciously quarantine villages if needed. His presence in the opera is certainly not random; audiences attending the opera in the 1830s would have recognized his character and his reasons for being in the village.

As seen above, red wine and solanum dulcamara were among the various marketable preventatives or cures for cholera. The opera’s itinerant medical man, Dulcamara, takes his name from one of these supposed pre-emptive treatments. Solanum dulcamara, or bittersweet, is a poisonous vine in the potato family that has a long history of medical use to slow the heart and calm the nervous system. If taken in too large a dose, though, it leads to dizziness, delirium, convulsions and death. Dulcamara’s name is original to Romani’s text for L’elisir; in Eugène Scribe’s libretto for the Daniel-Francois Auber’s French opera Le philtre on which L’elisir is based, the character is Dr Fontanarose (rose fountain).

As originally envisioned by Romani and Donizetti, Dulcamara was a far more complex and knowledgeable character than so many later, often comic interpretations, imply. He is, after all, working in the midst of an epidemic. Audiences in the 1830s would have been familiar with the cutthroat nature of the medical marketplace, where licensed medical men competed for patients by labeling their rivals as quacks, con men, and frauds. Clues in the opera suggest that Dulcamara was not a comic charlatan who takes advantage of naïve villagers. To begin with, medical historians would say that there was a fine line in 1832 between a quack and a licensed medical practitioner. Quacks relied on the same treatments and the same ingredients as regular doctors did. For example, cure-all elixirs were extremely popular throughout the nineteenth century, and by naming various diseases in his opening “Udite, udite,” Dulcamara demonstrates his extensive medical knowledge. Furthermore, the red wine Dulcamara sells Nemorino is typical of the wine-based tonics sold by medical men of all sorts under the generic name of elixirs in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. (See figure 3.) These would be marketed for a variety of reasons, including as prevenatives/cures for cholera and as love potions. Numerous examples of wine bottles decorated with hearts (confirming the latter) have been unearthed by archaeologists in Europe. So, by taking Dulcamara’s elixir, it can be argued that Nemorino could have been accomplishing two tasks in one: getting Adina to fall in love with him while also avoiding getting cholera.

Latest Comments

Have your say!