It’s not the end of the world. But with the coronavirus running rampant, you could be forgiven for thinking so. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse symbolically portray the four events that will occur before the end of the world – plague, death, famine, and war. The first two of these are currently striking fear into the hearts of men and women. How does God figure in all of this, a God that in classical Christian theism is both good and all-powerful?

We might view this particular plague apocalyptically as the beginning of the end and expect, as many Christians have for the past two thousand years, the imminent arrival of the Antichrist. He would be the archetypal evil human being, the son of Satan, who would come at the end of the world to persecute the Christian faithful before being defeated by Christ and his armies of angels. No shortage of candidates for this role, now as always.

That said, the coronavirus raises more general questions about the relation between God and evil. It is perhaps worthwhile, now more than ever, to consider the ways in which Christianity has tried to think its way through this relationship.

As often, the source of both much clarity and much confusion was Saint Augustine (354-430). There was in the thought of Augustine a tension that was never quite resolved – between the origin of evil on the one hand and the origin of sin on the other. This tension was imbedded in two sources of Augustine’s thought – on the one hand, his Platonism that accounted for evil in terms of ‘the absence of good’ and, on the other, his Biblicism that looked to the origins of evil in an historical event in the Fall of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

For Augustine, the goodness of God was philosophically vindicated, in spite of the evil in the world, by the overall harmony of the whole. Evils there might be, but they were all part of a divinely created and ultimately benevolent harmony. Theologically, the goodness of God was justified, in spite of his foreseeing that man (and some angels) would misuse their free will, by having planned that the ensuing moral (and natural evils) would fit into the overall harmonic perfection of the universe.

In the history of Christian thought, accounts of evil would peel off in two different directions – one that would optimistically view all evil as a necessary aspect of an ultimately harmonious universe, another that would pessimistically see all evil as the inevitable consequence of the original act of sin on the part of Adam and Eve.

The pessimistic position was exemplified in John Calvin (1509-64). As a result of the sin of Adam, declared Calvin, ‘before we saw the light of this life we were soiled and spotted in God’s sight.’ At best, Calvin’s God was a God of justice, duly punishing man by introducing pain and suffering into a world that he had originally created perfectly good. At worst, he was an angry, punitive despot, worthy of our respect, even of our fear, but not of our love. In either case, he was a God whom, after the Fall, it was difficult to see as essentially good.

The optimistic position was found in Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). He looked to the Platonic Augustine. In spite of evils, both natural and moral, this was still the best of all possible worlds. Moreover, in spite of appearances to the contrary, the world was ultimately good by virtue of its foundation in the essential goodness of God. But had Leibniz’s unfailing optimism and his firm belief in the divine goodness failed to take evil seriously enough?

The French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) thought so. But he thought evil far too serious to be taken seriously. It could only be treated satirically, as it was in his Candide, ou l’Optimisme (1759).

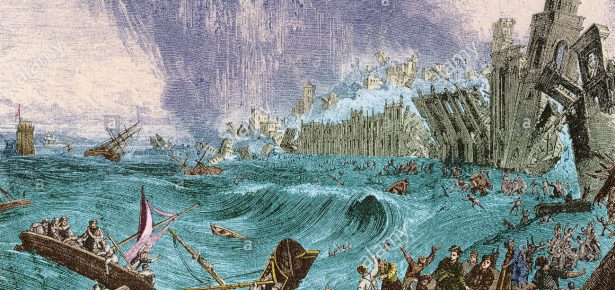

This book was motivated by one of Europe’s greatest natural disasters. On 1 November 1755, at 9.30 am, Lisbon was almost totally destroyed by an earthquake, followed by further tremors, fires, a tsunami, and civil unrest. It was All Saints Day, and large numbers of people were killed as churches collapsed upon them. Statistics for natural disasters, then as now, are notoriously rubbery. But anywhere from 20 to 40 thousand people died out of a population of 200,000. It sent shock waves, literally and metaphorically, throughout Europe.

In Candide, Leibniz was Dr Pangloss, an instructor in ‘metaphysico-theologico-cosmoloonigology.’ Now Pangloss was a committed believer in this world as the best of all possible ones, in spite of its natural evils and the moral evils perpetrated in particular by those of religious faiths (Christian, Jewish and Muslim). Whatever happened in the world, Pangloss, like Leibniz, was able to rationalise it as compatible with its being eventually for the best.

Voltaire’s view of the world was the consequence of seeing the horror of evil and human suffering for what it was – completely inexplicable. But it was not merely the existence of evil as such that rendered God’s goodness questionable. It was the sheer quantity and quality of it that provoked despair: ‘So far from the notion of the best of possible worlds being consoling, it drives to despair the philosophers who embrace it.’

What was Voltaire’s solution? Surprisingly perhaps, it was not despair, nor a quiet descent into a pre-modern version of angry if cultivated atheism. Rather, it was a gentle resignation, a philosophical que sera sera. There was to be, therefore, an avoiding of airy philosophical speculations on how to justify the ways of God to man (like this piece of writing!). It meant the quiet cultivation of our gardens as God had intended for us in the Garden of Eden before the Fall. There should be the doing of a little good in the hope of our becoming a little better.

This is a solution that may not satisfy believers in the goodness of God. Nor is it of much comfort to those who see the sufferings of this present time as sufficient to justify atheism. But it may resonate among those of us who, in isolation at home, are quietly tilling the soil, laboring in our vegetable patch, or contentedly mowing our lawns. Simple, but somehow satisfying!

Latest Comments

Have your say!