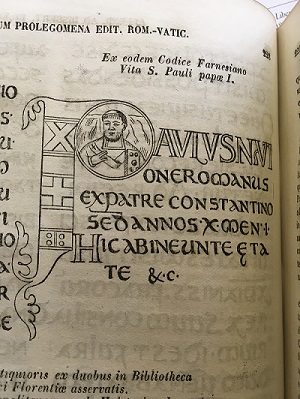

The rewriting of history to suit a current political agenda is not new. Nor is the creative representation of particular individuals or institutions only a modern phenomenon. The extraordinary serial biography of the ancient and early medieval popes known as the Liber pontificalis (Book of Pontiffs) is an example from the sixth century, composed within the papal administration in Rome; it was subsequently updated in the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries, so that the complete text extends from St Peter to Pope Stephen V (†891). In its representation of the apostolic and papal past of early Christian Rome, and its articulation of the Petrine succession and papal ideology, that were of such seminal importance for Latin Christendom, the Liber pontificalis was designed to shape both contemporary perceptions and the memory of Rome and the popes within western Europe. How effectively this text does so, and how then the impact of its remarkable combination of historical reconstruction, deliberate selectivity, and political use of fiction, might be established, are what I investigate in my book.

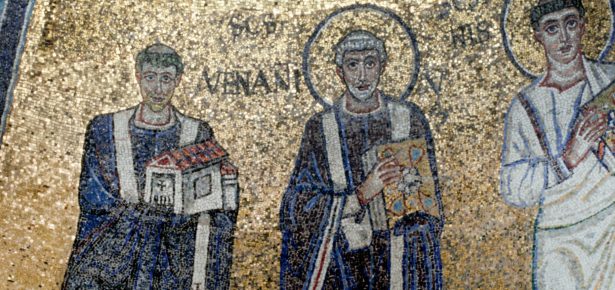

In choosing the word ‘invention’ in my title I mean first of all the original Latin sense of discovery as well as the more recent meaning of an original creation with a function. I am also deliberately invoking the rich seam of questioning immutable cultural traditions and apparently ageless institutions precipitated by Roy Wagner’s The invention of culture in 1975 (revised 2nd edition 2016) and Eric Hobsbaum and Terence Ranger’s The invention of tradition in 1983. Through the prism of the Liber pontificalis’s narrative, therefore, I examine the transformation of the imperial city of Rome into a holy city of Christian saints and martyrs, and how the text presents the visible power of the bishops of Rome within the city.

Anyone who visits Rome, immediately becomes aware of the unparalleled sense of continuity over two thousand years in the physical reality of the Eternal City. In addition to my many visits to Rome over the years to attend conferences, work in the Vatican library, and in field trips with my students, I have been fortunate enough to spend two longer periods of residence. Exploring Rome on foot in all its richness and variety, I wondered how the Franks (on whose history I have spent much of my academic career) might have perceived Rome, what I could reconstruct in my mind of the early medieval city the Franks would have known, and how they might have acquired knowledge of Rome even if they never actually went there. So much of our knowledge of any aspect of a place or its past is formed by texts, images and buildings. In the Franks’ case, one of the history books available to them was the Liber pontificalis, for despite its sixth-century Roman and papal origins, and seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-century Roman and papal continuations, most of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the full text are not from Rome, or even from Italy, but from the late eighth- and ninth-century Frankish kingdoms.

My research on this history book over the past decade was also in tandem with my teaching about early medieval Rome for a final-year History paper in Cambridge. The integration of research and advanced teaching of a succession of cohorts of outstandingly enthusiastic and critical undergraduates was the most wonderful stimulus. Apart from lectures and classes in Cambridge, the three-day field trips in early January with each year’s cohort, resident in the British School at Rome, extended our knowledge from the texts into the physical remains of early medieval Rome – buildings, frescoes, marble floors, brickwork, statues, and mosaics. This paper also precipitated my participation in two collaborative volumes, both published by Cambridge University Press: Rome across time and space: cultural exchange and the transmission of ideas, edited with Claudia Bolgia and John Osborne (2011) and Old Saint Peter’s Rome, edited with John Osborne, Carol Richardson and Joanna Story (2013).

Although much of my book looks at the potential power of the text deduced from its contents and the context in which it was produced, I also address the questions of dissemination and audience, and of the reception of the text. How were copies of the text made, preserved, used and read? I made a fresh examination of all the surviving codices of the Liber pontificalis from before the end of the tenth century, now in Bern, Brussels, Cologne, Den Haag, Florence, Laon, Leiden, Lucca, Milan, Modena, Munich, Naples, Paris, Turin, Valenciennes, the Vatican, Verona, Vienna and Wolfenbüttel. The text can be understood is as a representation of the popes as a virtual presence and as an important source of textual authority. It created an historical framework within which to understand all the other texts emanating from Rome which were so fundamental to the beliefs and practices of the Christian church. The text forged a new institutional identity, with the popes as active agents in the development of the papacy both as an institution and as the logical continuation and institutionalization of the work of Christ and his disciples. It set out to shape the time and context in which it is was written, by means of a particular representation of the past. It thus managed and manages the memory of that past.

Latest Comments

Have your say!