With live concerts suspended all over the world, among the casualties was a performance of Haydn’s oratorio The Creation by the ensemble Arcangelo at London’s Barbican Centre on 1 April.

When I noticed it on the calendar months ago, I chuckled. Not only would the concert neatly coincide with Haydn’s birthday on 31 March, it also harkened back to a historical moment: The Creation was featured in a gala 1808 performance in Vienna honoring Haydn for his 76th birthday. The composer, seated in an armchair, was carried into the hall through a standing, cheering crowd. Brass fanfares were sounded, adulatory poems were read, and “Haydn received from all who could get near him the sincerest proofs of high esteem.” [1]

Maybe Arcangelo’s birthday-related timing was just down to practical matters, but to me it looked like a mischievous wink. As co-editor of The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia, I spent the past several years writing, commissioning, shepherding, and editing Haydn scholarship, only to wrap up the monumental project at the very moment when the classical music world, in one giant fortissimo tutti, turned its attention to Beethoven, thanks to his great big, irresistibly round 250th birthday. Cue the Beethoven concert marathons, tours, exhibitions, pilgrimages, souvenirs, commemorative stamp, even a brand: #BTHVN2020.

On the other hand, perhaps Arcangelo planned to make strategic, coattail-riding reference to Beethoven. Certainly, scholars and commentators are fond of describing The Creation in see-how-Haydn-was-just-as-important-as-Beethoven terms. The work, particularly the extraordinary opening (“and there was light!”) is often said to epitomize the aesthetic category of the sublime – a category virtually synonymous with Beethoven – and to have served as inspiration for Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (in its musical imitations of nature) and the “Ode to Joy” lyrics of his Ninth (in its deist, even interfaith spiritual message).

In this narrative, the 1808 Creation concert also plays a relevant part. Some contemporary reports mention that Beethoven was in attendance, whereas by 1812 the story was embellished such that Beethoven was not just present but paying tribute. Embellishment became accepted detail: Haydn biographer H. C. Robbins Landon wrote in Haydn: A Documentary Study (1981), “Beethoven, the tears streaming down his face, bent and kissed the hand of his former teacher.” [2]

Around the same time that I became aware of Arcangelo’s concert, I read another (even cheekier?) response to the 2020 Binge on Beethoven. Writing in the Chicago Tribune, Smith College Professor Andrea Moore went so far as to suggest an all-out moratorium: “letting Beethoven’s music fall silent for the duration of his 250th anniversary year might give us a new way into hearing it live again.” This was meant to be thought-provoking, of course. Beethoven is already ubiquitous: to program more Beethoven is only to travel yet again down a well-worn path. Unprogramming Beethoven could lead to fresh ways of listening to Beethoven — and it could leave room in the concert hall for “a whole new cohort of composers representative of the world we live in now.”

And here we are, four months into what was to be Beethoven’s year: forget travelling any path, we’re not leaving the house. What’s ubiquitous is cancellations; concert halls are empty. Moore’s moratorium gambit was an abstract intellectual exercise. What has actually unfolded is a dire necessity, an unprogramming of an entirely different order.

Something much bigger than Beethoven is eclipsing Beethoven — along with Beethoven’s partial, temporary, and ultimately unimportant eclipse of Haydn.

Will this real moratorium give us new ears? Will we develop new cultural priorities? I think the answer is yes. For the moment though, I’m just trying to be a good citizen, staying at home.

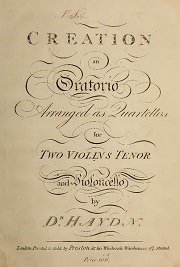

Here at home, I find myself thinking about what really made The Creation canonic, indeed what kept Haydn’s reputation alive when public interest otherwise waned in the nineteenth century: sheet music versions published for string quartet or piano and voice — that is, arrangements for amateurs to play at home. The Creation never left the repertoire, never left the public conscience, and as a result, neither did Haydn.

A similar story could be told of another monumental Haydn work: “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser,” written in honor of Emperor Franz II’s birthday in 1797, now the tune of the German national anthem. This was the epitome of a public-facing composition, its premiere — sung simultaneously in locations in and around Vienna, Hungary, and Italy — a marvel of dynastic propaganda. And yet soon it was heard in arrangements (including the String Quartet Op. 76, No. 3, second movement, and a set of keyboard variations) in private living rooms throughout Europe.

Haydn himself played it at home on his piano on a daily basis in his final, frail years.

A little over a month after his last birthday, on 10 May 1809 the French began their siege of Vienna. Haydn received a visitor: a French officer, who sang an aria from The Creation — paying his respect to Europe’s most celebrated composer, sheltering at home.

[1] Haydn’s contemporary biographer, Georg August Griesinger, quoted in Matthew Head, “Music with ‘No Past’?: Archaeologies of Joseph Haydn’s The Creation,” 19th-Century Music 23/3 (Spring 2000): 216.

[2] Cited in Christopher Wiley, “Mythological Motifs in the Biographical Accounts of Haydn’s Later Life” in Richard Chesser and David Wyn Jones, eds. Land of Opportunity: Joseph Haydn and Britain (British Library Board, 2013): 174.

Latest Comments

Have your say!