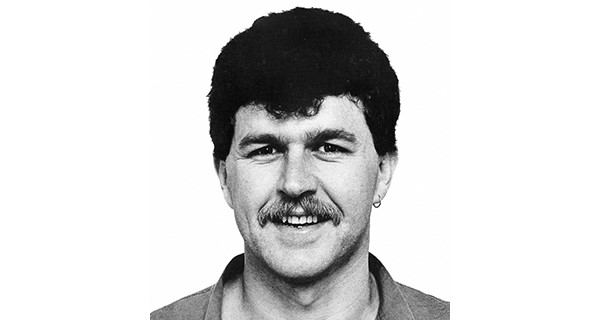

In November 1983 a twenty-nine-year-old man named Bruce Burnett returned to his homeland, New Zealand/Aotearoa, from San Francisco. Bruce hadn’t been in San Francisco long: he had left New Zealand in 1982, and when he came home he had swollen lymph glands and a persistent intestinal infection.[1] Bruce thought he might have AIDS. For several months he was depressed and unhappy, but in 1984 – as his friend Kate Leslie remembers – he ‘resurfaced and renewed and was imbued with zeal to do something about HIV/AIDS in New Zealand’.[2] Kate, who was the social work manager at Auckland Hospital, first met Bruce in August 1984, when he came to a meeting at the hospital’s STD department, and spoke to venereologists and infectious disease physicians about his knowledge of the disease. Kate and Bruce began to work together on HIV/AIDS education, ‘safe sex’ publicity, fund-raising, training sessions for counsellors, and establishing the Shanti programme – modelled on San Francisco’s Shanti project, where Bruce had done some training – to set up a network of volunteers to help people with AIDS. Bruce secured funding from the government to set up the New Zealand AIDS Foundation.

In the months between what Kate describes as his resurfacing from the depths and his death, on 1 June 1985, Bruce achieved what most of us would not be able to achieve in decades. (I don’t say ‘in a lifetime’, because a ‘lifetime’ is a highly variable length of time.) Kate and Bruce wanted to make sure that messages about safe sex got across to the population at large, and to the gay community in particular, and Kate knew from her experience in working with STDs and contraception that publicity using technical language and Latin terms did not reach everyone. Complicated language used in advice about contraception had resulted in unwanted pregnancies, and so Bruce and Kate wanted to make sure safe sex education was easy to understand.

I remember workshops held in Auckland in 1984 where a simple message was shared: two men having anal sex without a condom are at risk of passing on HIV infection. We all became intensely aware of HIV/AIDS, even though the number of cases in New Zealand remained small. This awareness was generated by talking, by advertisements, by a barrage of media stories. A country in which sex between men was still illegal, and which was very uncomfortable talking about sex, suddenly began asking how men might put their penises inside each others’ bottoms without infecting each other. Bruce and Kate’s legacy of plain speaking has remained important in all HIV/AIDS publicity in New Zealand. A 1997 advertisement from the New Zealand AIDS Foundation shows two men taking their clothes off. Their muscled torsos are visible, but their heads are hidden by the t-shirts that they are evidently in a rush to get rid of. The caption reads: ‘The dishes can wait. After five years together we still fuck with condoms.’[3] If you go to the New Zealand AIDS Foundation website, you learn that ‘New Zealand has a relatively low prevalence of HIV by international standards’, because of the consistent promotion ‘of condom and lube use for anal sex between men’.[4]

From the time of his resurfacing until the time of his death, Bruce went everywhere in New Zealand, talking on radio and on television and to groups of people, in particular groups of gay men, about HIV/AIDS. One of the things that made Bruce so powerful and effective was his calmness and openness: the matter-of-fact way in which he told listeners that he himself had AIDS, and that nobody coming into contact with him was in danger of getting AIDS. His voice calmed us all at a time when we all felt like despairing and panicking. I remember Bruce talking to me and other members of Auckland University’s gay students group in 1985, not long before his death. He didn’t seem like a person with a life-threatening illness: he was very alive, very alert, very persuasive, very passionate. But his presence made HIV/AIDS real to all of us. When the talk finished, we all hugged Bruce. I still remember that hug. Hugging Bruce was one of the most precious moments of my life.

A message-giver gives a message, but that message is only effective if a community is willing to listen. Bruce was not a Cassandra figure, because Kiwis listened to what he had to say. Knowledge of how to avoid infection saves lives. Bruce bore witness to the risks of HIV/AIDS: he told the story of his own illness in a way that made us understand the risks were real. If we did not practice ‘safe sex’, we were at risk of getting infected, and of infecting others before we were even aware of being infected ourselves. Now we isolate ourselves from others, both to save ourselves from infection by Sars-CoV-2, and to prevent ourselves from passing on infection to others. Our knowledge and our action are intimately related: we act differently because of what we know. We can no longer hug one another to show that we care: we show that we care by avoiding contact with others. How strange – to show how much we care for people by staying away from them! We are all staying in confined spaces, but our messages are not confined: we are communicating, as best we can, with others, and our actions, while isolating us physically, are communal in spirit.

The willingness of New Zealanders to listen to Bruce might be contrasted with the treatment of Li Wenliang, who on 3 January 2020 was officially reprimanded for having posted the ‘untrue statement “7 SARS cases confirmed at Wuhan Huanan Fruit and Seafood Market” on the WeChat Group “Wuhan University Clinical Class of 2004” on Dec 30, 2019’. Li was told he had committed ‘an illegal act’ and formally advised: ‘if you are stubborn, do not show repentance, and continue to conduct illegal activities, you will be punished by the law!’[5] Reading this caution against Li Wenliang, it is difficult not to think of Galileo being commanded in 1616 ‘to abandon completely … the … opinion that … the earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing’.[6]

Li Wenliang, like Bruce Burnett, went on to die from the infection he was warning others about. On 7 February 2020, Wuhan Central Hospital released a statement saying that Li Wenliang, who had been ‘unfortunately infected with coronavirus during his work in the fight against the coronavirus epidemic … died at 2:58 am on Feb 7 after attempts to resuscitate were unsuccessful’.[7]

In admonishing Li Wenliang, Wuhan police were making their own untrue statement, because the message he had shared with his WeChat group was true. Why do human beings not want to admit the truths of infectious diseases? On 25 April 2020, as I write, we can document many more cases of Covid-19 illness than the ‘7 SARS cases’ Li referred to on 30 December 2019. One website that collects data on the epidemic says there are now (25 April 2020) 2,833,011 confirmed cases, and that there have been 197,351 deaths.[8] (There are undoubtedly many more cases and deaths that have not been recorded.)

Why was Li Wenliang not listened to, instead of being punished for telling the truth, a truth wrongly described as an ‘untrue statement’? Some human beings seem unwilling to admit the power of infections diseases, naively believing, perhaps, that they are always the problem of others, never our own problem. Other human beings want to know everything they can about infectious diseases, so that we can avoid being infected or infecting others.

Knowledge, as we know, is power, but the suppression of knowledge is also power, a power that needs to be resisted. We cannot return to 30 December 2019. We can imagine what might have happened if Li Wenliang’s message was acted on rather than suppressed, but history is what happened, rather than what might have happened. Four months from now the figure of 197,351 deaths will be a historical figure. Will we be appalled at how many more deaths there have been, or relieved that there have not been as many deaths as we feared? If every contagious person and their contacts were effectively quarantined for long enough, might it not be possible to eliminate the virus?[9] (A person who has recovered from Covid-19 will no longer be infectious.)

The efficacy of our actions will depend on how good we are at listening to people like Li Wenliang and Bruce Burnett, on how well we communicate with each other, and how effectively we act on the knowledge we arrive at and share with each other. Listening, thinking and acting cannot bring back those we have lost. But it is never too late to do our best to protect ourselves and others. This is, perhaps, what the living owe the dead: a willingness to learn from what they have told us, from their true statements, the messages they have shared with us, a willingness to learn from their living, and from their dying. Dear Wenliang, dear Bruce, I am still listening to you.

______________________________________

[1] http://www.gaynz.net.nz/history/BruceBurnett.html (accessed 24 April 2020).

[2] http://www.pridenz.com/remembering_bruce_burnett.html (accessed 24 April 2020).

[3] Reproduced in Chris Brickell, Mates and Lovers: A History of Gay New Zealand (Auckland: Godwit, 2008), p 348.

[4] https://www.nzaf.org.nz/awareness-and-prevention/hiv/hiv-in-nz/ (accessed 24 April 2020).

[5] https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Exhortation_of_Wuhan_Public_Security_Bureau_Wuchang_Branch_Zhongnan_Road_Street_Police_Station (accessed 25 April 2020).

[6] Special Injunction (26 February 1616), in The Trial of Galileo: Essential Documents, translated and edited by Maurice A. Finocchiaro, Indianapolis: Hackett, 2014, p. 102.

[7] https://edition.cnn.com/2020/02/06/asia/li-wenliang-coronavirus-whistleblower-doctor-dies-intl/index.html (accessed 25 April 2020). It is possible that Li Wenliang died on 6 February, rather than 7 February: rumours of his death circulated widely before the initial announcement.

[8] https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed 25 April 2020).

[9] Consider the responses to Covid-19 of the state of Kerala and in Vietnam, where strict quarantining is made possible by communities working together, by mass mobilization. For Kerala see https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/21/kerala-indian-state-flattened-coronavirus-curve, and for Vietnam see https://www.thenation.com/article/world/coronavirus-vietnam-quarantine-mobilization

Latest Comments

Have your say!