On November 11, 2019, observers with a telescope and proper solar filters will be able to see a rare sight: a transit of Mercury across the face of the Sun. Transits occur when a planet passes directly between the Earth and the Sun so that, looking out from the Earth, we see the silhouette of the planet on the Sun’s disk. Only Mercury and Venus can transit the Sun because only these planets have orbits that lie inside that of the Earth. However, because their orbits are slightly tilted relative to Earth’s orbit we don’t see a transit every time one of those planets laps the Earth on its trip around the Sun. Instead, Mercury transits are visible only about 13 times per century and Venus transits are rarer still.

There are reports of transit observations stretching from the 9th century to the early 1600s, but it is now generally accepted that those observers actually saw sunspots (which were unknown before the advent of the telescope around 1610). The first definitive transit observation was of a Mercury transit on 7 November 1631. This transit had been predicted by Johannes Kepler using his new theory of elliptical planetary orbits. Astronomers set out to observe the transit, in part, to test Kepler’s theory. Although many attempted the observation, few were successful and only one, Pierre Gassendi in Paris, published his observations.

It’s not terribly surprising that so many astronomers missed the transit. Cloudy weather spoiled the opportunity for many. The uncertain timing of the event added yet another challenge. Even those who had clear skies and were looking at the right time were faced with the difficulty of observing the Sun, which could be done one of two ways: with a camera obscura (or pinhole camera), or by projecting an image of the Sun through a telescope onto a screen. One further problem with observing the transit was entirely unexpected: Mercury turned out to be much smaller than anyone thought.

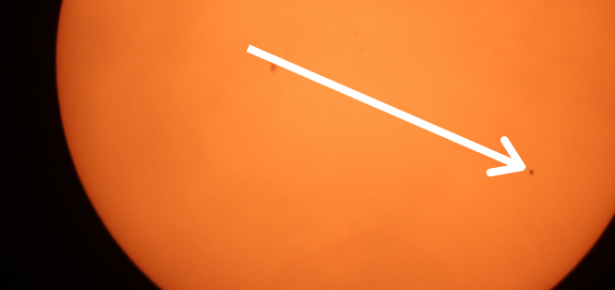

Figure 1: Transit of Mercury photographed on 9 May 2016 from Berry College, GA (USA). Mercury is the tiny black spot on the lower right. Some sunspots are also visible. Photo credit: Todd Timberlake

In 1631 there was still a great deal of confusion about the apparent (or angular) size of the planets. Naked eye observations of the planets suggested that, for example, Mercury when it is closest to Earth (as during a transit) should appear roughly one tenth the size of the Sun in diameter. In fact, Mercury is much closer to one hundredth the size of the Sun in diameter during a transit [see Figure 1]. The sizes perceived by the naked eye were really an artifact of the brightness of the planet and the optics of the eye and gave no indication of the true size of the planet at all. Early telescopic observations by Galileo and others had already shown that the true apparent diameters of the planets were much smaller than previously thought, but nobody had done a systematic study of this issue prior to 1631 and traditional naked-eye sizes were still accepted.

Figure 2: Gassendi’s diagram showing the motion of Mercury across the face of the Sun from Mercurius in sole visus & Venus invisa (1632).

The unexpectedly tiny size of Mercury doomed observers who were using pinhole cameras and it nearly caused Gassendi to miss the transit. He saw a dark spot on the Sun around 9 AM on 7 November, but he assumed he was just seeing a sunspot because it was, he believed, far too small to be Mercury. Thankfully, he continued to observe for several hours and noticed that the tiny dark spot moved much faster across the face of the Sun and along a different path than a sunspot would [see Figure 2]. The motion was consistent with predictions for the transit and Gassendi convinced himself, and eventually other European astronomers, that the tiny dot was really Mercury on the face of the Sun. Gassendi’s observations helped to correct the long-standing error regarding planetary sizes and also helped astronomers make slight improvements in Kepler’s orbital theory for Mercury.

On 11 November 2019 you can see a transit of Mercury yourself. You will need proper equipment to safely view the Sun, like a telescope with an approved solar filter. Unlike Gassendi, you now know what to expect: Mercury will appear as a tiny dot on the Sun’s face. Although the transit may not be visually impressive, seeing it happen in real time, and knowing that advances in human knowledge allow us to accurately predict such rare celestial phenomena, should inspire plenty of awe.

Latest Comments

Have your say!