Cambridge University Press Bookshop opened in 1992, but the shop itself has been around for a great deal longer and selling books all the while; since 1581, in fact. Passing from hand to hand over the centuries, 1 Trinity Street was taken over in 1846 by Daniel and Alexander Macmillan who employed their nephew, Robert Bowes, as an apprentice. He would later become partner and eventually take on the premises. The shop remained Bowes & Bowes until 1986 when it became Sherratt & Hughes before Cambridge University Press took it on in 1992. We are still going strong today, showcasing around 50,000 different titles in the shop. In 2008, we expanded round the corner into 27 Market Hill where we opened our specialist Education and English Language Teaching shop the following year. We are proud to continue the fine old tradition of selling books here and contributing our bit to the fine history of 1 Trinity Street.

This February we are celebrating the 100th anniversary of women in Britain being granted the right to vote. The Representation of the People Act, which became law on Feb. 6th, 1918, gave the vote to women over 30 who were occupiers of property or married to occupiers. Admittedly this was limited: although I would be enfranchised, some of my colleagues here at the shop would not. It would take another ten years for full women’s suffrage. That being said, it was a huge success for the women’s suffrage movement, which as we will see from some of my chosen Library Collection books this month, had been growing from strength to strength in the years leading up to World War I.

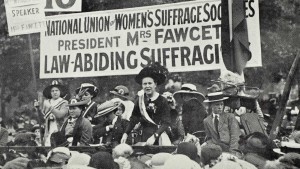

First up is The Woman Question in Europe (1884), a collection of essays from women across Europe who were involved in the positive progress of the ‘woman question’. It’s a well-intentioned and fascinating bit of comparative social history. In her chapter on electoral rights in Britain, Millicent Garrett Fawcett outlines the contemporary state of women’s suffrage in England. The name of Fawcett may be familiar to you: this pioneering feminist has recently been in the news, being favoured to be the first woman to have her statue in Parliament Square – ahead of Baroness Thatcher (and indeed Emmeline Pankhurst who is in nearby Victoria Tower Gardens). She was also one of the founders of Newnham College here in Cambridge. As well as contributing to this comparative study, she’s the author of another of our texts, Personal Reminiscences, which looks back on the suffrage movement and its achievements from 1920 (more of which below).

Fawcett reminds us that women were asking for enfranchisement only in those cases where they met the same conditions as those men who had the vote, i.e. held property. The 1880s marked a phase in the suffrage movement where mass demonstrations and peaceful rallies were becoming commonplace; suffrage, previously the concern of the educated and higher class women, was now moving from an intellectual pursuit into the “rank and file of women themselves” (p. 15); from drawing room to town hall and beyond. It is a reminder, however, of the fact that it was still necessary for the women’s case to be argued by men in parliament. There were some strong voices in their favour (notably JS Mill), but at this stage the prevailing sense was frustration. Remembering this helps to explain the militancy of some twentieth century suffragettes.

Next is Margaret Mary Dilke’s Women’s Suffrage, first published in 1885. From 1878 Dilke was an active member of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, and later treasurer of the Central National Society for Women’s Suffrage. Written at the same time, but in a very different tone from Fawcett, Dilke’s is a rapier-sharp book in which she challenges and takes-down the major anti-suffrage arguments and nonsense that were spouted in certain quarters of the contemporary political scene: “women have suffered at least as much from the ignorance of men as to their real wants and wishes, as they have from any deliberate intention of legislating against them” (pp.26-7).

If we come to think of it, the amount of civility and attention now paid by men to women in society is not so very extensive. If men wait on women in public, do not women always wait on men in private? And they will certainly continue to cook the dinners, and warm the slippers, and lay the newspaper, all cut and folded, at the man’s elbow, even should they afterwards find time to read that newspaper themselves. (Women’s Suffrage, p. 31)

In an excellent precursor to the famous 1912 poster What a Woman may be, and yet not have the Vote, Dilke writes: “It has often been remarked that the law classes women with infants, criminals, and lunatics; but even in that doubtful company she holds an inferior position. A minor grows to manhood before many years are passed, a criminal resumes the rights of citizenship as soon as his sentence has elapsed, a lunatic may recover and vote as before; but a woman, do what she will, is always excluded. A fortune may be left her; she may attain celebrity in literature, art, or science; she may be upheld as a model of all the virtues; she may devote herself to her country, and pour out her wealth for its benefit—but a vote she has never any hope of reaching.” (Women’s Suffrage, p. 50)

This is a far more scathing indictment of the anti-suffrage movement than the previous work, but it is supposed to be. Dilke was politically astute and angry; the book is fast-paced and a pretty exciting read. She would be great on Twitter, describing “politicians whose brains are not distinguished for lucidity” (p.56) and stating “the rights of parents over their children are certainly very simple, if not very just. One parent, the father, has all the rights. The other, the mother, has none” (p.67). Indeed, the chapter “Women’s Grievances” should be required reading for all people today who don’t use their vote. It’s brilliant and furious stuff, yet full of clarity and succinctness of message.

My final pre-war text is British Freewomen: Their Historical Privilege (1894, 3rd edition 1907), by Shakespeare scholar and feminist, Charlotte Carmichael Stopes. This is a concise history of British women’s legal and civic rights and how they have varied over the centuries. It was a pioneering work which became a key text used by women’s suffrage activists to justify their position. “The privilege of British Freewomen remained a recognised quantity for ages, though that quantity became ‘small by degrees and beautifully less,’ it was not finally annihilated till the heart of the nineteenth century.” (p.24)

As our other writers have done, Stopes takes particular interest in the combination of property and sex as reasons for exclusion from the voting franchise: “What is simply unjust when individuals are selected on the basis of sex, becomes both illogical and unjust when questions of sex are imposed on those of property” (p.28). She recounts the facile arguments made against women’s suffrage on the basis of their lack of strength or understanding; their inability to understand maths or the classics; their not-heavy-enough brains; the fact that they are not Shakespeare, Beethoven, or Raphael. Still, Stopes writes, at least it’s not as bad today as it was one hundred years earlier, when:

As our other writers have done, Stopes takes particular interest in the combination of property and sex as reasons for exclusion from the voting franchise: “What is simply unjust when individuals are selected on the basis of sex, becomes both illogical and unjust when questions of sex are imposed on those of property” (p.28). She recounts the facile arguments made against women’s suffrage on the basis of their lack of strength or understanding; their inability to understand maths or the classics; their not-heavy-enough brains; the fact that they are not Shakespeare, Beethoven, or Raphael. Still, Stopes writes, at least it’s not as bad today as it was one hundred years earlier, when:

“An eldest son that received all the inheritance and privilege had therewith to support the women of his father’s family as well as of his own. It was disgraceful for him as well as for them that they should earn no money. But they gave him labour, acting as upper servants, butts of ridicule, as the case might be, or blind worshippers when all the outer world had learned to disbelieve in him.” (p. 208)

I am reminded of the term “spinster cluster” here, used to describe the leftover genteel women cut out of inheritances and with no way of earning money who banded together in groups of relatives and close friends in similar positions to pool their resources. It’s an arrangement seen time and again in the novels of, for example, Jane Austen. It is higher education which Stopes believes brought women to the point where they are now independent enough of men to earn their own livings, albeit for less pay, although they are still oppressed “by man’s power of place, which gives him power of veto; by inherited thought-fallacies and linguistic inaccuracies; by the nature of the medium through which things are seen.” (p.204).

It is generally accepted that it was World War One that finally brought the political and social state of Britain into the right climate to accept women’s suffrage as expedient and necessary. The last couple of books were written after the war, after the 1918 Act, and when enfranchisement was moving towards its next hurdle: full adult suffrage (achieved in 1928).

By 1917 the Government and country were “face to face with the impossible position that if circumstances necessitated an appeal to the country there was in existence no register of voters which could in any sense be looked upon as representative of the manhood of the nation,” all that was left being “the elderly, the infirm, the shirker, the crank who had remained at home evading military service, and ‘the conscientious objector.’ (The Women’s Victory, p. 122)

We return first to Millicent Garrett Fawcett whose book, The Women’s Victory – and After, Personal Reminiscences, 1911–1918, outlines how the tide finally turned towards the women’s vote in 1918.

Highly critical of parliament which, in 1912, seemed “scarcely capable of giving intelligent attention to any subject unless it is forced to undertake the excruciating pain of thought by the demands made by voters in the constituencies” (p.40), Fawcett is nevertheless a moderate and non-militant.

By 1917 it was the time for the women to come forward again, having played it quiet for a few years, using their various organisations to support the war effort and replenish the domestic workforce. But a new obstacle arose, namely that if they were granted the vote on the same footing as the men, which they had always demanded, then they would far outnumber the male electorate. This is where the 30 years or over rule came in. Hugely objectionable to suffragists, it was never the less accepted as necessary: “The thirty years age limit for women was quite indefensible logically; but it was practically convenient in getting rid of a bogie whose unreality a few years’ experience would probably prove by demonstration. We remembered Disraeli’s dictum, ‘England is not governed by logic, but by Parliament.’” (The Women’s Victory, pp.142-3)

Circumstances and decades of work had arrived at this point in 1918 with the limited extension of the franchise and women “no longer treated either socially or legally as if they were helpless children” (pp.153-4). As Fawcett goes on to outline, though, the struggle was not over, with the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship in 1919 listing the following aims:

I leave you to assess for yourself how effectively those demands have been met a century later.

Last but by no means least, let’s have a look at the Letters of Constance Lytton, first published in 1925 and edited by her sister, Betty Balfour. Lady Constance was a suffragette of the more infamous kind: brave and influential she not only used her position to influence politics at a high level, but also took to the streets, disguising herself as a working-class woman and undergoing hunger strikes and force feeding in order to experience and expose the physical struggle on the street-level of the suffrage movement. These diaries, although incomplete, give a striking and moving first-hand account of the movement through all levels of society and the disparity of the treatment of the women from different classes.

Con (as she is referred to in this book) became gradually involved in militant suffrage movement, having begun in October 1908 by visiting its members, including Emmeline Pankhurst, in prison and offering her support. As the movement spread and having witnessed the social inequalities in the way that women in prison were both treated and sentenced, she had become militant herself, writing in April 1909: “How can modern educated women agitate? The thing is unthinkable. But oppose them with a touch of uncivilised barbarity; to even a small extent make martyrs of them;—and the thing is made easy for them at once.”

Con (as she is referred to in this book) became gradually involved in militant suffrage movement, having begun in October 1908 by visiting its members, including Emmeline Pankhurst, in prison and offering her support. As the movement spread and having witnessed the social inequalities in the way that women in prison were both treated and sentenced, she had become militant herself, writing in April 1909: “How can modern educated women agitate? The thing is unthinkable. But oppose them with a touch of uncivilised barbarity; to even a small extent make martyrs of them;—and the thing is made easy for them at once.”

She continued to work tirelessly for the movement until she suffered a stroke in 1912. She had recovered enough to begin her book Prisons and Prisoners in 1913. She completed this in 1914 before the outbreak of the War and the change of tactics that brought an end to the militant suffrage protests. Con remained active in her efforts to help various causes through the war and afterwards, although she was physically unable to do much. She died in 1923.

These books give the reader a real sense of how exhausting and demoralizing it must have been for these women and supportive men arguing their corner for suffrage against such deeply-engendered misogynies and illogical fallacies. As we enter the next 100 years, let’s look forward to building on these hard-won rights for women across the world.

You can learn more and follow the Cambridge University Press Bookshop here:

Website: http://www.cambridge.org/about-us/visit-bookshop

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CUPBookshop/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CUPBookshop

Latest Comments

Have your say!