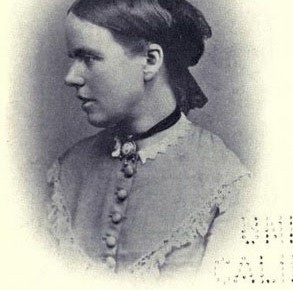

Julia Wedgwood via archive.org and University of California

In Darwin and Women, I quoted Emma Darwin’s letter to Henrietta: ‘Snow has been both agreeable and entertaining. Yesterday we read aloud her pamphlet on suffrage, which a good deal converted Wm [William] and me.’ Snow was Emma and Charles’s niece Julia Wedgwood. I later looked up her pamphlet, Political claims of women, published by the National Society for Women’s Suffrage in 1875 or 1876.

In the pamphlet, Julia argues that working women should have the vote on the same terms as men (i.e. there would be a property qualification).

In the pamphlet, Julia argues that working women should have the vote on the same terms as men

‘A class of unrepresented workers has not the same advantages as one which is represented … more than 3,000,000 women are ill-educated and ill-paid workers. These women have to support themselves, and those dependent on them … One woman in three remains unmarried, and the majority of these have to earn their own bread. … The question whether a sheltered home or the busy world is a woman’s ideal sphere has no bearing upon them.’

This clearly has a bearing on Darwin’s view that women were not, as a rule, breadwinners. I wondered where Julia got her figures from, and tracked down a likely source in the report on the 1871 census, available here.

The report lists 3,453,681 women ‘of specific occupations’ in England, contrasted with 3,948,527 wives, the two groups being treated as exclusive, which the report admits was problematic though in practice unavoidable. (‘Scholars’ were also excluded.) It’s worth noting that three of these women of specific occupation (there’s a breakdown by age) are under 5, and 9,929 between 5 and 10 years old. The total population of England is given elsewhere as 21,299,683. The commentary, which is on the whole very positive about the prospects for working women, was as follows:

‘As girls and women of all ages now constitute more than half of the population of England, their occupations are of vital importance. 3,948,527 are wives, and a large proportion of them are mothers. This is a noble and essential occupation, as on it as much as on the husband’s labour and watchfulness depend the existence and character of the English race. But in all stages of human progress, women have had, besides these, other employments; among savages they perform the most laborious work; and in Europe now they are seen burdened and toiling in the fields, as women were once found toiling underground in English mines. Engaged in spinning and weaving in the heroic times, in cookery and surgery in the age of chivalry, their employments are now becoming infinitely diversified; a married woman of industry and talent aids her husband in his special occupation, or she follows different lines of her own; even when she has children this is possible, for it is only in a few cases that the whole of a wife’s lifetime is filled up with childbearing, nursing, and housekeeping. Women unmarried, always exist in great numbers and will continue to exist at all ages, who devote themselves to works of utility or charity, and to the arts, for which they have a taste, in which they often display extraordinary talent, and for which they get as well remunerated as men. In literature and song women have always excelled. There are certain walks of athletic life from which women are inflexibly excluded; whether with advantage, without drawbacks, it is difficult to say, as many of the finest children are produced by hard-working women. They are also excluded wholly or in great part from the church, the law, and medicine; whether they should be rigidly excluded from these professions, or be allowed—on the principle of freedom of trade—to compete with men, is one of the questions of the day.’

Julia doesn’t tackle Darwin’s comments on women in Descent of Man (published in 1871) directly in her pamphlet, but one of her remarks casts an interesting light on them. Countering the charge that female suffrage would give the clergy undue influence, she agrees that in novels women are often swayed by clergymen, but adds that in real life it is by no means usually the case. ‘People are apt, in making up their minds on any subject of social interest, not to think of the men and women they know, whom there is always a curious but inexplicable tendency to classify as exceptions, but of some abstract type of the character supposed, and fiction is a large source of this kind of general opinion.’ Darwin was himself a keen novel reader, with a preference for pretty heroines and happy endings.

Latest Comments

Have your say!