Participants:

Kathleen M. Hilliard is the author of Masters, Slaves, and Exchange. She is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Iowa State University. She received her BA from Wake Forest University and her PhD from the University of South Carolina, where she worked under the direction of Mark M. Smith and won the Wienefeld Award for the best dissertation in history. Since 2006 she has studied and taught about the Old South, slavery, and the social and cultural contradictions of antebellum America at the University of Idaho and Iowa State University. Portions of her work have been published in major essay collections and presented in scholarly meetings in the United States, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom. She has served on the Editorial Board for Agricultural History and Gale/Cengage’s ‘Slavery and Anti-Slavery’ digital history project.

Susanna Michele Lee is the author of Claiming the Union. She is Associate Professor of History at North Carolina State University, where she specializes in nineteenth-century American history, especially the Civil War and Reconstruction. She received her BA in History and Psychology at the University of California, San Diego, and her MA and PhD in History from the University of Virginia. Lee has taught at the University of Virginia, the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and Wake Forest University. Active in the burgeoning field of digital humanities, she has served as the project manager for the digital archives The Valley of the Shadow, The State of History, and North Carolina in the Civil War Era. Lee has received fellowships from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and the Virginia Historical Society. She has also participated in a National Endowment in the Humanities summer seminar on the ethnohistory of Indians in the American South at the American Indian Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Robert E. May is a Professor of History at Purdue University. He is the author of Slavery, Race, and Conquest in the Tropics (2014); Manifest Destiny’s Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America (2002); John A. Quitman: Old South Crusader (1985), winner of the Mississippi Historical Society’s book prize; and The Southern Dream of a Caribbean Empire (1973). He is editor of The Union, the Confederacy, and the Atlantic Rim (1995).

Laura F. Edwards is the author of A Legal History of the Civil War and Reconstruction. She is the Peabody Family Professor of History at Duke University. Her book The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South was awarded the American Historical Association’s 2009 Littleton–Griswold Prize for the best book in law and society and the Southern Historical Association’s Charles Sydnor Prize for the best book in Southern history.

Barton A. Myers is the author of Rebels against the Confederacy. He is Assistant Professor of Civil War History at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. His first book on American Civil War guerrilla warfare Executing Daniel Bright: Race, Loyalty, and Guerrilla Violence in a Coastal Carolina Community, 1861–1865 won the 2009 Jules and Frances Landry Award for the best book in southern studies published by Louisiana State University Press. Myers has written articles and/or book reviews for George Mason University’s History News Network (HNN), H-Net’s H-CivWar and H-South, the Civil War Book Review, the Journal of American History, Common-Place, the Civil War Monitor, the Journal of Southern History, the Journal of the Civil War Era, Army History, the North Carolina Historical Review, the Journal of American Nineteenth Century History, and Civil War History. He is the recipient of a grant from the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, a Russell Weigley grant, and a Mellon research fellowship.

Moderator: What do you see as the most important moment of the American Civil War?

Susanna Lee: The most important moment of the Civil War, in my judgment, occurred when enslaved people first escaped to Union lines and found refuge there. These moments, as they recurred over and over again, started a revolution. The United States initially pledged not to interfere with slavery in the Confederacy. Slaves who ran to Union lines, however, placed abolition on the wartime agenda. Soldiers and officers were confronted with a choice: they could allow slaves to stay in camp and accept their assistance in waging war against the Confederacy, or they could send them back to their masters and mistresses who would attempt to use them to support the Confederate war effort. Soldiers and officers allowed slaves in Union lines with General Benjamin Butler serving as the most well-known example. The Union armies then became forces of emancipation. Slaves provided the initiative that ultimately culminated in the Confiscation Acts, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Slaves’ efforts in running to Union lines and offering their services as laborers and as soldiers helped to ensure that the Union preserved in the war would be fundamentally transformed, recognizing not only black freedom, but also black citizenship.

Barton Myers: The most important moment of the U.S. Civil War was not the same moment for every American. More than thirty-one million people lived in the United States of America when South Carolina left the Union in December 1860. Roughly nine million of those people lived in the seceding states that would eventually form the Southern Confederacy in February 1861. Nearly four million black southerners were slaves living in peonage inside the Confederate and Border-South states that grew the nation’s number one export: cotton. The most important moment of the American Civil War differed for the many people of the Union and Confederate states, but for the individuals living in perpetual bondage in the American South, the moment that they became free was clearly the most important moment of the war. Some were freed at the point of Union Army bayonets, as soldiers occupied and liberated. Other slaves took matters into their own hands and freed themselves by running to the Union lines. More than 180,000 black men would eventually serve in the Union Army, for many of these men the moment they put on the blue uniform was a deeply transformative political act. Without the victory of Union arms and Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, an enormous expansion of federal power constitutionally justified by the military necessity of preserving the Union, and which abolished an entire form of private property in the areas still in rebellion, the status of the newly free people would have been precarious. Indeed, many would not have taken the bold step of liberating themselves without the assurance of such a proclamation.

Barton Myers: The most important moment of the U.S. Civil War was not the same moment for every American. More than thirty-one million people lived in the United States of America when South Carolina left the Union in December 1860. Roughly nine million of those people lived in the seceding states that would eventually form the Southern Confederacy in February 1861. Nearly four million black southerners were slaves living in peonage inside the Confederate and Border-South states that grew the nation’s number one export: cotton. The most important moment of the American Civil War differed for the many people of the Union and Confederate states, but for the individuals living in perpetual bondage in the American South, the moment that they became free was clearly the most important moment of the war. Some were freed at the point of Union Army bayonets, as soldiers occupied and liberated. Other slaves took matters into their own hands and freed themselves by running to the Union lines. More than 180,000 black men would eventually serve in the Union Army, for many of these men the moment they put on the blue uniform was a deeply transformative political act. Without the victory of Union arms and Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, an enormous expansion of federal power constitutionally justified by the military necessity of preserving the Union, and which abolished an entire form of private property in the areas still in rebellion, the status of the newly free people would have been precarious. Indeed, many would not have taken the bold step of liberating themselves without the assurance of such a proclamation.

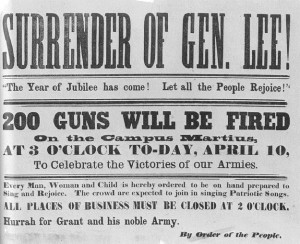

For white southerners, a politically divided population, the defeat of the Confederacy became one of the most important moments they would remember from the war. Wherever white southerners were when they received the news, Richmond, Montgomery, Raleigh, their experience diverged widely, but it was no less profound. For it was from the ashes of the defeat that the South created the powerful Lost Cause mythology, which completely revised the cause, interpreted the meaning, and recast the southern heroes of the war. Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson became infallible figures for the majority of ex-Confederates, part of a coping mechanism to explain that military defeat. The myth would be enshrined forever in films like Gone With the Wind. Indeed, the mythology wiped away dissent within the southern population. For those white southerners who fought against the Confederacy from within, the first national Conscription Act in American history passed by the Confederate Congress in April 1862, was perhaps the most important moment of their war since it sent the state to the doorstep of every white military-age male compelling his service. As a result of this policy, thousands of anti-Confederate citizens and southern unionists eventually engaged in militant resistance and guerrilla war against the Confederacy. It was in this wartime experience when many people saw their male family members ripped away from them and carried off to war that they vested their most important Civil War memory.

Freedom, slavery, family, Union, victory, defeat, and liberation were all at stake during those four years

For white northerners, the victory of the Union armies was a triumphal moment only to be quickly replaced with mourning for the loss of President Lincoln, felled by an assassin’s bullet just days after the surrender of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in April 1865. Many of the soldiers who served in the victorious Union armies and defeated Confederate armies would return home, like many veterans, changed by war, but they would look to different moments when they saw their baptism-by-fire as the most pivotal, exciting, and important moment. Battlefield service at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and Petersburg would be unforgettable life-altering events for these men. Some soldiers would look to the loss of a commander or friend on one of those fields as the most important moment, seared into their memory for all time. For many civilians North and South, the return home of their loved ones or the death of their most beloved would be the critical moment they remembered from the war. In so many ways, the question of the most important moment of the American Civil War tells us what was most important to the American the question was posed to in 1861-1865. Freedom, slavery, family, Union, victory, defeat, and liberation were all at stake during those four years. The transformative moment that closely reflected what was at stake on a personal level was the one a Civil War American remembered as most important to them.

Laura Edwards: I agree with Susanna Lee that the most important moment in the Civil War was when African Americans left slavery for Union lines. In doing so, as Lee writes, African Americans “placed abolition on the wartime agenda.” But I see that moment less as a single point in time and more as a series of moments that collectively altered the meaning the Civil War because they also fundamentally transformed the nation’s legal order. That transformation ultimately involved all Americans, not just enslaved African Americans.

When enslaved African Americans escaped to Union lines, they simultaneously freed themselves and underscored the difficulties of ending slavery as a legal institution. We often assume that efforts of individuals to obtain freedom would inevitably result in the abolition of slavery in law throughout the entire United States. But that leap—from individual claims to a structural change in the nation’s legal order—was much less certain than it would appear at first glance. Individuals could be free without changing a legal order that sanctioned slavery—thus the situation of free blacks in slave states. In fact, it was possible to recognize the freedom of some or even all enslaved people without eliminating the institution of slavery in law, a situation that would make it possible to resurrect elements of slavery in some form or another at some future point in time. The history of race relations after the Civil War, particularly in the state of the former Confederacy, suggests a political context in which such a possibility was not out of the question.

Nor was emancipation solely a matter of political will, despite the tendency to portray it in those terms, particularly in the popular culture of our time. As a result, we often think that the greatest barrier to emancipation was convincing the nation’s political leaders to see slavery as wrong. That was a formidable barrier, to be sure. But it was not the only one. The nation’s political leaders could do nothing about emancipation until they confronted a legal structure that gave the federal government very little power over the legal status of individuals, which included whether individuals could be enslaved. It was generally agreed that states had legal purview over those issues. The federal government could enact measures that discouraged slavery, but it could not unilaterally abolish slavery. Federal officials could persuade state governments to outlaw slavery, and Lincoln pursued that strategy. But there were limitations to such an approach. States could refuse to comply, recreating a situation in which slavery remained in some states and not in others. Kentucky—which remained in the United States during the Civil war—rejected abolition right before the end of the war, making it difficult to imagine that states of the former Confederacy would ever agree to end slavery without compulsion if they re-entered the United States. Emancipation, moreover, could be uncertain even in states where it was abolished. If it were accomplished through legislation, it could be repealed, should the political winds change. Abolition was more secure if written into state constitutions, which were more difficult to alter. But states wrote new constitutions at infrequent, but regular intervals, opening up the possibility for future change. The only way federal lawmakers could end secure emancipation throughout the entire United States was to change the U.S. Constitution.

The U.S. Constitution was amended, with the Thirteenth Amendment, which did abolish slavery everywhere in the United States. What began with enslaved African Americans reaching for new lives ended in structural changes to the nation’s legal order. Federal policy responded to the actions of individuals. Ultimately the implications extended well beyond those who sought freedom from slavery. The Thirteenth Amendment solidified an expansion of federal authority present in other wartime measures, but that might otherwise have contracted once the military crisis passed. More than that, it became the first of three Reconstruction Amendments that gave the federal government more power over the status of all American citizens and that connected the federal government to the American people in new, unprecedented ways.

Robert May: I believe there were two equally important moments determinative of the outcome of the Civil War. The first was Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863–which amounted to a nearly final guarantee the European powers would refrain from entering the war in league with the Confederacy. It also quickly led to an exponential increase in the contribution of African Americans North and South to the Union military effort. Approximately 180,000 black soldiers eventually served in the Union army during the Civil War, the overwhelming number of them enrolled after the Emancipation Proclamation. Moreover, almost 30,000 blacks served in the Union Navy, greatly enhancing the manpower of the North’s power at sea.

The second of these moments was the point when Lee’s decision to invade Pennsylvania, made a few months after the Proclamation, became irreversible. The ensuing battle of Gettysburg was a catastrophic blow to Confederate manpower and morale. Had Lee remained in Virginia and adopted a more Fabian strategy in 1863, he could perhaps have avoided disastrous defeats, strung out the war, and induced enough war weariness in the North as to undermine Lincoln’s campaign for reelection in 1864. It is well known that Lincoln’s reelection in 1864 was uncertain through most of the the summer of 1864, even with the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg the year before. Although the Democratic candidate in 1864, General George McClellan, refused to run on his party’s peace platform, it is unclear whether he would have had the will to crush the Confederacy if elected. One has to wonder, given his longstanding reluctance to risk high casualties in battle and his deep qualms about both emancipation and taking the war to civilians, whether a President McClellan would have unleashed Grant and Sherman in 1864 the way Lincoln did. Without aggressive Union military strategies in 1864-1865, the Confederacy might have hung on long enough to eke out a fragile independence.

Perhaps most interesting, in all our responses, is the common emphasis on emancipation, though we approach emancipation from varying perspectives. It seems to me that this very commonality is a fascinating window into how Civil War historiography has shifted over the last half century. I suspect that scholars answering the same question half a century ago would have mostly honed in on different moments, most of them occurring on battlefields.

Kathleen Hilliard: As Robert May notes, we seem to be driving in the same direction here. There is no doubt that emancipation—through individual flight, military order, or constitutional amendment—serves as the fundamental “moment” of importance in the war. But I think we need to understand the choices enslaved African Americans made not only in concert with the actions of Republican congressmen and Union soldiers, but alongside the decisions made by white Confederates and their kin as well.

Later this week, my students and I will sit down to discuss the fourth chapter of W.E.B. DuBois’s brilliant Black Reconstruction in America. In this too often misunderstood work, we see DuBois at his finest as historian, sociologist, and political theorist. Here he offers a unique argument for Confederacy’s fall: a “general strike” joining white and black southern working men and women on the battlefield and the home front that spelled disaster for the slaveocracy. He stresses the political choice made by enslaved men and women to withhold labor from the Confederacy—making their way toward Union lines, dragging “with perplexed and laggard steps” (66) a recalcitrant US government. But, crucially, DuBois takes his interpretation a step further, noting that by late 1863, poor white southerners were making political calculations of their own, laying down their arms quite deliberately and heading for home. Lost cause writers and neo-Confederates have called this cowardice or treason, but DuBois saw it for what it was: a full-throated assertion that the Stars and Bars wasn’t worth fighting for.

At once bitter rivals and unwitting allies, striking black and white southern men and women doomed the planters’ world. Their thousands of brave and desperate actions—and we need to know so much more about these—culminated in a moment of revolutionary crisis. Understanding the political choices ordinary southerners made to stand against slavery by withdrawing their labor deepens and transforms our understanding of the Civil War itself.

Robert May: Kathleen Hilliard’s excellent most recent posting, it seems to me, speaks to current political debates as well as Civil War historiography. One argument I constantly encounter from questioners, when speaking to public audiences, is that Confederates were not fighting for slavery, but for states’ rights, to defend their homes, and that sort of thing. Of course, it is simplistic to claim that the Confederacy was only about slavery. But one way to demonstrate that it was mainly about slavery is to emphasize both that Confederates had to resort to a draft in 1862 and that many non-slaveholders gave up on the cause mid-war. As historians we have a duty, I think, to confront neo-Confederates with hard facts when we get the opportunity. The current court controversy over the specialized Sons of Confederate Veterans’ license plate in Texas reminds us how many modern Americans venerate a cause dedicated to slavery and racial subordination, in many cases purposely but also often unknowingly. It is the latter ones that historians especially need to engage as a step towards improving racial understandings in this country.

And let me add regarding DuBois’s Black Reconstruction that I consider myself extremely lucky that Robert Starobin exposed me to its arguments and evidence while I was in graduate school, at the outset of my career in the profession. I was profoundly influenced by the work at the time, and continue to believe it one of the most valuable books on the Civil War Era, one that deserves far more attention than it gets today.

Susanna Lee: I appreciate the ways the posts bring attention to the various aspects of emancipation from individual choices of enslaved people, nonslaveholders, soldiers, commanders, and politicians to the effects on wartime diplomacy to structural changes in the legal order. A powerful illustration of Barton’s reminder about the “deeply transformative political act” of black military service is Spotswood Rice’s letter to his daughters and their mistress. A visual illustration of Laura’s point that emancipation was a “series of moments” is the Digital Scholarship Lab’s Visualizing Emancipation. Future commenters seeking to minimize the significance of emancipation will have to grapple with a large body of work by scholars on this topic and the trove of documentation uncovered by them.

Scholarship reflects larger social and cultural changes in our understanding of “war” and how we conduct war that were also part of the Civil War

Laura Edwards: It is interesting that recent scholarship, as reflected in our posts, has focused on emancipation, rather than the military battles of the war. That situation does reflect changes in the scholarship, with recent histories integrating a wider range of people (particularly African Americans and women of both races) as well as wider array of issues (including those that used to be categorized as social, cultural, and even political and legal and, therefore, distinct from the military conflict). But it strikes me that the scholarship, in turn, reflects larger social and cultural changes in our understanding of “war” and how we conduct war that were also part of the Civil War. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people tended to define war primarily in terms of military battles. The Civil War was key in changing those conceptions. The Union Army targeted the civilian population, and the wartime policies of United States tried to destabilize the Confederacy’s social order, with the Emancipation Proclamation being the most famous example. Later, the United States pursued a plan to remake social relations in Confederate states, thus extending the meanings and implications of war further. For its part, the Confederacy mobilized the entire population in support of the war effort, nationalizing key parts of economy and reaching into peoples daily lives in unprecedented ways. Yet I think that historians now focus on those aspects of the Civil War, because of the experience of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, in which wars further blurred the lines between the military and the civilian population and defined the military’s goals in terms of mediating and, often, remaking social relationships on the ground. They also framed the conflict in terms of competing ideologies and cultures, which required something other than just military victory to reconcile. If we see “war” differently as scholars, it is also because we are reflecting larger changes around us.

Barton Myers: I like both Robert and Laura’s points about the importance of our changing definition of “war” and its impact on our debate about the Civil War’s meaning/consequences. This is born out even by the changes in the field of military history itself over the last few decades. Civil War military historians no longer examine just the conventional, symmetrical field of battle to tell the story of victory and defeat in the war. They also now examine military occupation, guerrilla violence, atrocity, terrorism, and the experience of warriors off the conventional field of battle—a war that occurred also on an asymmetric battlefield and that involved people of very diverse backgrounds. Military scholars now look at mobilization and demobilization, soldier motivation, and a range of cultural factors in shaping the militaries.The exploration of the war’s military moments has also expanded to include the personal decisions of U.S. Colored Troops from the North and South. The militant resistance among the Confederacy’s own population is now recognized as a major problem for the Confederacy’s war effort, playing a role in its defeat. Indeed, the expansion of our cultural understanding of war in the past several decades has forced scholars of the Civil War (and many other conflicts) to do a better job of asking broader and more insightful questions about why the war ended with Confederate military defeat and the surrender of the Confederate government in only four years (unlike the War for Independence, which lasted far longer). All of these new areas of analysis bring us much closer to understanding the transformation that the war brought for the U.S. government and the American people.

Moderator: Who was the most important figure in determining the War’s outcome?

Barton Myers: President Abraham Lincoln was ultimately indispensable in the role of Commander-in-Chief. Though Lincoln was largely an autodidact in military affairs, his perseverance and wise decision-making ensured the ultimate outcome of the American Civil War. Perhaps his most important military decision relating to the war’s outcome was his selection of Ulysses S. Grant to command as General-in-Chief of the U.S. Armies. The war’s ultimate outcome can be attributed to the military strategy implemented by Grant after he is elevated in March 1864 to full Lt. General. Grant would be the first person to hold the confirmed rank since George Washington. General Grant and President Lincoln’s overall strategic plan of moving each of the major Union armies in the Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia theaters, coupled with renewed operations in the Gulf South in the spring, summer, and fall of 1864, eventually brought about the surrender of the Confederate government in early 1865. This new military strategy placed maximum pressure on the Confederate armies in the field and helped break the back of the Confederate War Department’s attempt to supply the manpower and resources necessary for Confederates to continue their war effort. Along with this new strategy, Grant shifted to a war of attrition against the Confederate main armies as opposed to a narrow war of position, which had the end goal of merely seizing Richmond. While General Robert E. Lee searched for a battle of annihilation, one victory that would destroy the Union army, Grant and Lincoln’s more patient, if costly, strategy prevailed. As part of this military strategy, Lincoln and Grant utilized General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army, which seized Atlanta and ultimately brought an important military victory that ensured Lincoln’s 1864 reelection. In short, the successful tandem of Lincoln and Grant were the key decision makers in the war’s outcome.

Barton Myers: President Abraham Lincoln was ultimately indispensable in the role of Commander-in-Chief. Though Lincoln was largely an autodidact in military affairs, his perseverance and wise decision-making ensured the ultimate outcome of the American Civil War. Perhaps his most important military decision relating to the war’s outcome was his selection of Ulysses S. Grant to command as General-in-Chief of the U.S. Armies. The war’s ultimate outcome can be attributed to the military strategy implemented by Grant after he is elevated in March 1864 to full Lt. General. Grant would be the first person to hold the confirmed rank since George Washington. General Grant and President Lincoln’s overall strategic plan of moving each of the major Union armies in the Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia theaters, coupled with renewed operations in the Gulf South in the spring, summer, and fall of 1864, eventually brought about the surrender of the Confederate government in early 1865. This new military strategy placed maximum pressure on the Confederate armies in the field and helped break the back of the Confederate War Department’s attempt to supply the manpower and resources necessary for Confederates to continue their war effort. Along with this new strategy, Grant shifted to a war of attrition against the Confederate main armies as opposed to a narrow war of position, which had the end goal of merely seizing Richmond. While General Robert E. Lee searched for a battle of annihilation, one victory that would destroy the Union army, Grant and Lincoln’s more patient, if costly, strategy prevailed. As part of this military strategy, Lincoln and Grant utilized General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army, which seized Atlanta and ultimately brought an important military victory that ensured Lincoln’s 1864 reelection. In short, the successful tandem of Lincoln and Grant were the key decision makers in the war’s outcome.

Susannah Lee: As a historian who examines the past from the bottom up, I can’t name just one figure responsible for determining the war’s outcome. Instead, I choose one set of people: Union soldiers. The United States clearly possessed the resource advantage at the outset of the war. Being able to fully mobilize resources for the war effort, however, was not a given. The strategy that won the war relied on mobilizing a large number of soldiers for the battlefield. Enough soldiers volunteered for service or complied with conscription and then stayed in the ranks even with enormous casualties to win the war. African American soldiers, despite experiencing significant discrimination, served in large numbers in the latter stages of the war. This mobilization depended on the support not just of the soldiers themselves but also of civilians, especially soldiers’ fathers, mothers, and wives.

Soldiers were important not just in reference to the war but also to the peace that followed. Soldiers as the quintessential patriotic citizens possessed a claim on the government. Political leaders rewarded veterans (and their wives) with pensions. Black men’s service as soldiers also created space to consider their fitness for citizenship and its rights and privileges. As Frederick Douglass insisted, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” Black loyalty did not convince Republican politicians entirely to embrace black suffrage, but it opened up the possibility. The ultimate “outcome” of the war depended not just on victories on the battlefield but also the terms of Reconstruction.

Kathleen Hilliard: The easy answer here is Abraham Lincoln because of the way he transforms the war from a conflict over federal union to a quest for emancipation. That answer, though, like other popular runners up—Robert E. Lee, whose offenses in 1862 and 1863 wasted Confederate manpower, or Jefferson Davis, whose failure to devise an effective strategy doomed the Confederacy, or Ulysses S. Grant who pushed men forward when others faltered—presumes that the Confederacy was not doomed by the time they fired the first shot. I think it probably was. And so, the outcome of the war was probably foreordained. That said, however, I would turn back to Lincoln who, in November 1863, explained the war’s meaning in a more profoundly transformative way than many have fully grasped. His assertion, in the Gettysburg Address, that the republic had failed and that a new, more perfect union had to be built on the basis of government of the people, by the people for the people, is one we still struggle to realize, both in meaning and in fact. If southern slaves and soldiers broke the Confederacy’s back, Lincoln’s revolutionary jeremiad—his call for a new birth of freedom—made the war’s outcome meaningful as not simply the end of slavery and sectionalism, but the beginning of a more desperate and aspirational struggle for equality, democracy, and economic and social justice.

Robert May: I dislike opting for the obvious, but I think there are many reasons why there is a broad consensus that Lincoln was the greatest U.S. president. Most of these reasons, in turn, relate in some way to the Union’s victory in the Civil War. My emphasis would be on the following: (1) that despite his lack of military experience as compared with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, Lincoln usually demonstrated superior instincts in determining and molding Union grand strategy in the war; (2) that he chose excellent men for his cabinet who in turn made crucial decisions determinative of Union victory (e.g. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase’s innovative ways of financing the war effort); (3) that Lincoln handled the emancipation question extremely wisely, especially in the timing of his Proclamations so as not to alienate the four slave states still in the Union during the war’s early going; (4) that he responded appropriately to the very real challenges of wartime dissent (I find Mark Neely’s Fate of Liberty persuasive here); (5) that historians are increasingly crediting Lincoln with an important role in Union diplomacy and giving him very high grades, despite a few missteps, in this realm; (6) that far more than his Confederate counterpart, he was able to inspire his public with oratory so that Northern civilians would sustain an increasingly costly war effort. To be sure, Lincoln had his faults and not all of his decisions had favorable outcomes. His wartime Reconstruction efforts, for example, mostly failed. But overall, his contributions towards Union victory dwarf those of other figures worth considering.

One could build a competitive case for Grant or argue that Davis was the war’s “most important figure” because the mistakes he made helped sink the Confederate cause, but I would keep Lincoln in the spotlight, partly because scholars like William Cooper in recent years have convincingly restored Davis viability as a leader.

Laura Edwards: I always have trouble with questions that ask to identify a single most important person because I think that the actions of individuals become meaningful only in context—a context that, in turn, is shaped by many people. Given that, I’d like to do something that political leaders (those people usually identified as the important historical actors) are known for doing, which is changing the question to talk what I would rather talk about: the actions of people who we don’t usually think about at all when considering the war’s outcome, namely ordinary white women in the Confederacy. By ordinary, I mean white women whose families owned small farms or shops, not white women in the planter class. These women sacrificed an enormous amount for the Confederacy. But, contrary to current conceptions and much of the scholarship, they did not do so silently or passively. Rather, they thought that they had a say in how their society was governed—and as such, they are crucial in understanding the war’s outcome.

Take the situation in Salisbury, North Carolin in 1863, when a large group of very determined women marched through the streets. Between fifty and seventy in number, they were the widows and wives of Confederate soldiers who could no longer feed their families. So off they went to the railroad station where they heard that a merchant – a speculator, as they termed him – had stored some flour. The agent at the station tried to keep them out, insisting that there was nothing there. But he was no match for a passel of angry women, who came armed with hatchets and knew how to use them. As an eyewitness described it, they stormed past him and into the station. “The last I saw of the agent, he was sitting on a log blowing like a March wind.” (Presumably, that meant he had been rendered as pointless as a winter wind come spring, howling loudly, but to no real effect.) The women “took ten barrels, and rolled them out and were setting on them, when I left, waiting for a wagon to haul them away.”

Such actions, often led by women, took place all over the Confederacy in 1863. Observers then and historians now have explained women’s actions primarily in terms of desperation—and there was desperation aplenty to go around at this point in the war, when the Confederacy was short of pretty much everything. But bread riots also have a lot to do with both the precarious state of the Confederacy’s basic governing structures and the difficulties of rebuilding the social order afterward. And they were as much about women asserting their views of what they thought was right as they were about opposition to the government.

As the war dragged on, Confederate leaders kept extending government authority, reaching deep into the daily lives of everyone within its jurisdiction, appropriating their labor, property, and lives for the nation, and leaving little for anything else. Yet the legitimacy of government—at all levels—kept deteriorating, because it could not deliver on its promises. As the Salisbury women explained, they could afford government prices for flour, referring either to the set price that the Confederate government paid for goods or its policies that made surplus provisions (a largely theoretical concept in 1863) available to the families of soldiers at prices below market value. These women felt entitled to government prices, as citizens of the Confederacy who had given so much to their nation’s war effort. Yet government – be it local, state, or federal – could not deliver. So the women took matters into their own hands, certain of the legitimacy of their actions and with the expectation of community support. It was an accurate assessment of the situation. No one – not even the feckless railroad agent – stopped them as they raided the station in broad daylight, rolled their flour barrels out to the street, and waited patiently for transportation.

The Salisbury women followed the example of their leaders. They applied the principles of decentralization, assumed the mantle of legal authority, and acted on their own conceptions of what the law prescribed. So did many others in the Confederacy. The resulting conflicts further eroded the Confederate government’s legitimacy – and ultimately undermined governmental authority at all levels, resulting in distrust and disillusionment that undermined the war effort and also shaped attitudes toward government after the Civil War. When we ignore these people—and their ideas about what the social order should look like—says a great deal about how the war unfolded and how it ended.

Moderator: What were the global implications of the American Civil War?

Barton Myers: This is a big question with implications for many areas diplomacy, economics, trade, foreign relations, but I’ll just emphasize some of the military dimensions.

In many ways the American Civil War can be thought of as a world war fought primarily on American soil. The enormous impact of immigration is one area where a global connection can be seen on many American battlefields. Only about 45% of the Union Army during the war was made up of American-born people of British ancestry. The Union Army was a global army. While the German (216,000 born abroad) and Irish (200,000) immigrants tend to receive most of the analysis because of their sheer numbers there was representation from most of western Europe and the rest of North America and even a small number from countries in Asia. Thousands of Poles, Mexicans, Canadians, French Canadians, English, Dutch, Italian, and many from the greater Jewish diaspora found their way into the Union Army between 1861-1865. The Union Army and Navies also had 210,000 African-Americans and included some 4,000 Native Americans by 1865. The lack of global diversity in the Confederate Army (more than 90% born in America) tells us quite a bit about the importance of the Union’s definition of freedom, republicanism, and economic opportunity.

Many immigrant soldiers even formed their own regiments identified by ethnically descriptive garb, flags, and symbols. The 79th New York Volunteer Infantry “The Highland Regiment” was predominantly Scottish. The 69th New York Volunteer Infantry was part of the famed “Irish Brigade,” which was part of the disastrous assault on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg in December 1862. The 58th New York “Polish Legion” was, yet another. Confederates also had a handful of ethnically Irish units like the 17th Tennessee (CSA), but these were much more rare. And, some prominent, if more rare, foreign-born commanders like General Patrick Cleburne of County Cork, Ireland fought with the Confederates.

In addition to military talent from abroad, the war was also a global arms race with factories and dock yards in Europe scrambling to provide millions of small arms, edged weapons, ships, and other weapons of war for export to the Union and Confederate armies. More than 900,000 1853 Pattern British Enfield Rifles alone were imported.

The war was also fought on a global scale. There were naval battles off the coast of France and on the Atlantic, and a raid across the border from Canada by Confederates into Vermont. The June 1864 battle between the CSS Alabama and the USS Kearsarge off the coast of Cherbourg, France ended in the sinking of the famed Confederate commerce raider. The CSS Shenandoah, a notorious commerce raider in the Pacific, eventually surrendered in Liverpool, England with the ship subsequently sold to the Sultan of Zanzibar shortly thereafter.

It left a global military legacy as well. Many Confederate officers ended up in the armies of Mexico, Brazil, and elsewhere in Latin America. Some of the most famous to flee the military defeat of the South were John C. Breckenridge, Matthew Fontaine Maury, and Jubal Early. The subsequent impact of Confederate defeat caused thousands to flee to Central and South America, even today the descendants of those people in Brazil “Los Confederados” hold celebrations of their connection to the Confederacy. Following the war, European armies would study the implications of the American Civil War from Sandhurst and Saint Cyr to the Prussian Military Academy. This was, in part, a by-product of the many foreign visitors who watched the Civil War’s battles as official, international observers. Even from a strictly military perspective, the global implications of the war were enormous.

Susanna Lee: Sven Beckert’s work is instructive here. The Civil War reshaped the global cotton economy and created new global networks of labor, capital, and state power. The war caused manufacturers to look elsewhere for cotton, including India, Brazil, and Egypt, and also spurred imperial endeavors to insure reliable sources. The Civil War necessitated that cotton planters invent new forms of labor to replace slavery. Former slaveholders in the United States South worked out a system of sharecropping with freed people. This system ultimately became economically coercive through labor codes, crop liens, and debt quagmires. These workers–some as in the case of most African Americans in the South embarking on their lives as freed people–had to deal with an economy in which they would be subject to fluctuations of the world market. This new system of labor emerged around the world in India, Asia, and Egypt as well as the United States. The state supported this new system of labor through laws and regulations.

Robert May: The global implications of the Civil War were profound, especially for Europe, Latin America and British North America but also for other parts of the world (for instance, the war was the backdrop for the 1862 Anglo-American treaty for more effective suppression of the African slave trade). As the war began, foreign nations had to weigh the legality under international law and risks of recognizing the Confederacy and/or providing it with aid in the face of Union threats of war. Further, they had to decide whether to obey or defy the hastily proclaimed Union blockade of Rebel ports, knowing that the consequences either way would be serious. When European powers decided to respect the blockade, they ensured shortages of cotton imports from the South, which in turn triggered, by 1862, serious dislocations in the economies of several cotton-dependent European powers (especially Great Britain) leading to shifts in global trade and production patterns. British leaders incentivized increased cotton production in alternative locales like India and Egypt. Neutral shipping interests, wool producers, and certain other economic sectors abroad, on the other hand, enjoyed a kind of “war dividend” because of the cotton shortage and the way Confederate privateers crippled the U.S. merchant marine. European colonies in the Caribbean boomed as way-stations in Confederate smuggling efforts. Europeans by the many thousands enlisted in Union and Confederate forces (about a quarter of all Union soldiers were born abroad). For Irish nationalists, or “Fenians,” service in the Union army was often seen as a way to prepare militarily for eventual service back across the Atlantic in the cause of Irish independence from Britain. European observers flocked to the war for many reasons, partly to learn how the conflict was affecting military tactics, strategies, and tactics.

The Union’s victory greatly inspired upholders of democracy, republicanism, and nationalism abroad, while dispiriting upholders of aristocracy, conservatism and monarchy

And this was just the tip of the iceberg. With Union and Confederate military resources absorbed by the fighting and neither North or South in any position to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, the war provided an opportunity for European nations to reassert their imperial ambitions and quest for commercial dominance in Latin America. By the time the Civil War was a year old, Britain, France, and Spain had intervened militarily in Mexico under the pretense of collecting past-due debts, and Spain had re-annexed the Dominican Republic. Later on, French emperor Napoleon III capitalized on U.S. weakness to establish a puppet regime in Mexico. Britain’s provinces in Canada could not escape being drawn into the war in different ways, requiring significant military reinforcement from England at times of Anglo-Union crisis like the Trent affair. Confederate agents used Canada as a base for subversive activities in the North, including plots to rob northern banks, liberate Rebel captives in Yankee prisons, and burn New York City. In 1864, Anglo-Union relations tensed considerably when U.S. forces crossed the boundary in pursuit of Rebel raiders. Scholars agree that the course of the Canadian provinces towards ultimate independence was hastened by the U.S. Civil War.

Historians rightly emphasize the impact of Lincoln’s Emancipation proclamations, especially the final one of January 1, 1863, and the disintegration of slavery in the South through self-emancipation by slavery’s victims, on the entire world. It is easy to imagine slavery persisting well into the twentieth century in places like Cuba and Brazil, had its abolition in the United States not occurred under the duress of war. Lincoln’s death by assassination in 1865 was mourned throughout much of the world, in no small part for his role in emancipation.

Just as important, the Union’s victory greatly inspired upholders of democracy, republicanism, and nationalism abroad, while dispiriting upholders of aristocracy, conservatism and monarchy. The Lincoln administration, though infringing some civil liberties during the war, had nonetheless held wartime elections– even a presidential one–and mostly maintained press freedom. Most important, it had demonstrated by raising enormous armies and navies, harnessing military technologies, innovating in fund-raising, and rallying mass public support, that, despite the skepticism of many European aristocrats, democracies and representative governments have the will and potential to triumph in times of national crises and foreign threats. France knew better than to keep its Mexican venture going once Richmond surrendered.

Laura Edwards: I agree with the other posts that highlight various global implications of the Civil War. But I want to open up another global aspect of the Civil War, namely the solidification of the United States as a cohesive nation with jurisdiction over territory that reached from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast. While those dynamics unfolded within the boundaries of the United States, they were fueled by and representative of larger, global currents.

There are two elements here, both involving nationalism and the role of nationalism in consolidating the power of nation states. Before the Civil War, the United States, as a nation, formed an ambiguous part of people’s identities as Americans. They spoke of “these United States” or the Union, referring to an entity that was less a coherent nation than it was a coalition of separate states. People expressed their relationships to government in similar terms, identifying themselves as citizens of their states or even their hometowns as often as they did as citizens of their country. By the end of the war, those rhetorical constructions had become more singular and definitive: Americans were now citizens of the United States. That new construction was most clearly articulated by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address, with its powerful image of a newly consecrated nation, one built on the past but remade in the crucible of war: “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” Various policy changes in the United States during the Civil War gave institutional form to these national aspirations, providing the federal government the legal authority necessary to represent the nation and to connect the people to the nation in ways that had not been possible before.

The nation Lincoln invoked in the Gettysburg Address, moreover, was continental in reach, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific and incorporating that vast space into a single, unified jurisdictional entity. That United States bore little resemblance to the one established by the Founding Fathers. It emerged during the war years, as federal policy lured settlers west and cleared the way for their arrival by subduing and eliminating Indian nations that also claimed that land. Traditionally, historians have treated the imposition of federal authority in the West separately from the Civil War, the historiography of which is arrayed along a north-south axis, focused on the eastern part of the country and dealing with policies relating to the former Confederacy and the status of African Americans. Recent scholarship, however, has challenged that separation, arguing that federal policy in the West should be seen as an extension of the Republican Party’s vision of national unity. A continental view of the nation, one that includes areas where people did not wish to be a part of the national project, also changes the terms of the analysis, making it impossible to mask the coercive dimensions of that national vision. The nation did not just “extend” its reach; it did so through the conquest of foreign nations, which were purposefully denominated as something other than nations so as to make conquest appear as the inevitable march of progress in the history of the United States—the only nation with legitimate claims to the continent.

In this sense, the Civil War was about dynamics that were anything but unique to the United States. It was an upheaval connected to trends that marked the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries more generally: the power of nationalism and its place in extending and solidifying the authority of nation states.

Robert May: Professor Edwards makes some provocative points here. I would add that the national consolidation at the expense of native peoples that she describes also had the potential to go further southward. Lincoln’s wartime black colonization program for Latin America, a more serious vision than some scholars acknowledge, certainly had global implications involving remaining European colonies as well as independent states. Central American governments, partly because of memories of private U.S. invaders called “filibusters” in the 1850s, were unwilling to give green lights to the Lincoln administration’s schemes. As a result, the Union’s colonization efforts wound up reduced to a pitiful resettlement effort, that entirely failed, on an island off Haiti’s coast.

Kathleen Hilliard: Like Susanna, I immediately thought of Beckert’s recent discussion of the war’s impact on the global cotton economy and the accelerated rise of state-sponsored capitalism. Since she’s covered that so well, let me offer comments on pushback to that system. In late 1864, on behalf of the International Workingmen’s Association, Karl Marx sent Abraham Lincoln congratulations on his re-election. The “red sea of civil war” and the destruction of the slaveocracy, Marx hoped, would wash away northern workingmen’s hesitancy to support their European brethren in a global struggle “to attain the true freedom of labor.” The Civil War was impetus for radical movements around the world. The violent overthrow of slavery in the United States inaugurated more strident and focused criticism of a broadened definition of unfree labor—including wage slavery. In the United States, we see the birth of the National Labor Union in 1866, quickly followed by the Knights, the AFL, the Wobblies, and eventually the communist party, unionism growing bigger and demanding more. These movements were the radical culmination of the almost failed American “experiment” with democracy, which Union troops rescued on the battlefield. That lesson was long remembered as national civil war exploded into global class war stretching from Paris and Chicago in the 1870s and 1880s to Russia in 1905 and 1917 and even giving birth to a Lincoln-inspired Republic of China in 1911.

Moderator: We saw the reunification of the United States and the extension of rights to minorities–but is there an unexpected way in which the Civil War reshaped America?

Barton Myers: There were many, from the changes in the financial and currency system and the disruption in the geography of states to the profound social disorder to the lives of veterans. But, I’ll focus on one important revolution in military affairs that came as an unexpected result of four years of civil war.

One of the unexpected ways the Civil War changed the United States military was in the development of a formalized code that would govern America’s armies for the next roughly four decades. President Lincoln issued General Orders No. 100 or Francis Lieber’s Code in April 1863 to address some of the most difficult issues of combatant and non-combatant treatment during a war that brought more people into contact with military forces than ever before in the United States.

As the challenges of guerrilla warfare, prisoner of war treatment, and war fought among the civilian population took on new scale and importance for the Union army, Lincoln’s General-in-Chief Henry Halleck sought out America’s leading legal mind Francis Lieber to engage these thorny questions. Eventually, Lieber would head a group of writers that drafted the document that would be an all important guide for Union officers in the field. The magnitude of the problems experienced by generals in the field in 1861 and 1862 eventually led, under the code, to an outright ban on the use of torture by the U.S. Army as well as the discussion of a variety of other limitations on how combatants and non-combatant treatment should be defined and handled. The U.S. Army would frequently struggle in applying the code and often violated it during the many wars with Native American nations and in the Philippines in the decades following the Civil War, but the Civil War forced the development of clear legal parameters and a new ethical framework to govern the conduct of military affairs in the United States. The Lieber Code would become a starting point for the modern discussion of laws of war in both Europe and America in the late 19th and early 20th century, and subsequently, the basis for the Hague Conventions. With that in mind, its reverberations and its attempts to control excessive violence even during the Civil War, it was an unexpected but very important change to the thinking about the nature of warfare in both America and Europe.

Robert May: Given the myriad changes wrought by the war–some temporary, others long-lasting–it is difficult to isolate any one unintended change. To give an example, the wartime absence of strict constructionist southern Democrats from the U.S. Congress enabled passage of nationalizing legislation that had been obstructed by slave state lawmakers for years, including homestead, transcontinental railroad, and land grant college laws as well as much higher protective tariffs in support of industry. Northerners, in contesting secession did so primarily to preserve the Union, not to capitalize legislatively on a moment of opportunity in Congress. Nor did either Yankees or Rebs, in going to war at Charleston harbor in 1861, do so thinking it would necessitate drafts, a transformation of gender roles, income taxes, the repression of civil liberties, and so on–but such were just a few of the unintended results of going to war. Neither Northerners nor Southerners waged war consciously to create more industrialized, technologically-advanced, bureaucratized societies. Yet that was the result.

Robert May: Given the myriad changes wrought by the war–some temporary, others long-lasting–it is difficult to isolate any one unintended change. To give an example, the wartime absence of strict constructionist southern Democrats from the U.S. Congress enabled passage of nationalizing legislation that had been obstructed by slave state lawmakers for years, including homestead, transcontinental railroad, and land grant college laws as well as much higher protective tariffs in support of industry. Northerners, in contesting secession did so primarily to preserve the Union, not to capitalize legislatively on a moment of opportunity in Congress. Nor did either Yankees or Rebs, in going to war at Charleston harbor in 1861, do so thinking it would necessitate drafts, a transformation of gender roles, income taxes, the repression of civil liberties, and so on–but such were just a few of the unintended results of going to war. Neither Northerners nor Southerners waged war consciously to create more industrialized, technologically-advanced, bureaucratized societies. Yet that was the result.

Still, I’m convinced the greatest unintended result of the war was its massive number of casualties. Few Northern or Southern leaders, or their respective publics, anticipated a drawn-out war with mass casualties when they contested Fort Sumter in 1861. Fewer than 2000 U.S. soldiers had died in action or from their wounds in the U.S.-Mexican War of a decade and a half earlier; fewer than 12,000 U.S. soldiers died of disease in that same conflict. Many Southerners expected to get away with secession peacefully, or that their supposedly superior military traditions would ensure an easy victory if war came or, at worst, that European powers, because of “King Cotton,” would rush to save the Confederacy if things got too dire. Many Yankees expected that a single battle would do the Rebs in. Did any Americans, in the winter of 1860-1861, anticipate over 700,000 dead should the sectional conflict descend into civil strife? And who anticipated the mass number of wounded veterans returning from the war–so many that amputees would be a common sight in U.S. cities and towns well into the twentieth century. One could follow this train of thought into many corners, such as how the casualty rates led to revolutionary transformations in battlefield evacuation, hospitalization, military diet, prostheses, medical knowledge, and pensions. Surely no one in 1861 anticipated the political power that veterans, North and South, would wield in the decades after the war. To understand how far the war contradicted the expectations of 1861, one need go no further than ponder the story of the veterans.

Kathleen Hilliard: I’ve always been struck by the way in which—for good and mostly ill—the South was made by the Civil War. Certainly, regional identity was nothing new to nineteenth-century Americans, but it is interesting to think about the particular ways in which the war seemed to homogenize diverse constituencies in the region…and how that simplification has been embraced regionally, nationally and globally. If we look at the balance sheet of war, the confederacy “lost.” But the culture that has grown up—and was consciously constructed—around that loss has, strangely, has had enormous appeal. Internally, the “lost cause” gave white southerners something to rally around in the face of wrenching social and economic subversion. It allowed them to smooth out the rough edges of their history and to craft a politically useable past out of reality’s ashes. In short, they twisted up southern history and have sought to make it coterminous with Confederate history. Perhaps that’s not surprising —but the fact that so many others eagerly appropriated that culture of defeat certainly is. In her fantastic book Creating a Confederate Kentucky, Anne Marshall examines white Kentucky’s post war attempts to tap into this identity, though unionist sentiment before and during the war kept them from secession. As Nina Silber and other have noted, northern travelers and writers saw romance in Confederate ruin. And even today, the Confederate battle flag flies as symbol of not just racism, but unity and solidarity in secession movements and soccer stadiums across the world.

The most lasting effect of the Civil War has been the triumph of the federal ideal. However much this state or that may shout for secession in defense of culture and regionalism, at the beginning of the 21st century the United States is and will be inseparably one.

These aren’t the only narratives, of course, and the globalized and globalizing reality of the South in the 21st century has done much to challenge lingering nostalgia. In spite of neo-Confederate grousing, resurgent anti-Washington feeling, and a disingenuous embrace of “heritage,” however, the most lasting effect of the Civil War has been the triumph of the federal ideal. However much this state or that may shout for secession in defense of culture and regionalism, at the beginning of the 21st century the United States is and will be inseparably one.

Robert May: Your final comment, here, has me pondering not only how the war underlay a regional white identity or identities transcending the antebellum sectionalism of Calhoun and company, but also how its legacy influenced some of our greatest twentieth century writers. I suppose that William Faulkner would have authored great fiction had he not been obsessed with his Civil War ancestors, but perhaps not.

Susanna Lee: We think of the Civil War as a controversy between North and South. Expanding our vision continentally to encompass the West reveals unexpected ways that the war reshaped America. Of course, the Civil War originated, in part, over a controversy over slavery and westward expansion. In the aftermath of the Civil War, with the ascendancy of the free soil principle, former enemies agreed on westward expansion. The West was a key component of reconciliation. Many whites understood the attempt to conquer the West as a national priority that would help restore unity and heal the wounds from the Civil War. Former enemies continued to struggle after the war over Reconstruction policies. But there was significant agreement on the “Indian question.” Reconciliation between former Unionists and former Confederates contributed to an acceleration of attempts to subjugate Native Americans, to dispossess (and in some cases re-dispossess) them of their land, and to subordinate them to national authority.

The answers, including my own, mostly seek to explain why the Union won, particularly crediting Abraham Lincoln, rather than why the Confederacy lost. A couple of the answers engage internal explanations of Confederate defeat through reference to Robert E. Lee’s costly aggressiveness and Jefferson Davis’s political challenges and most fully (in Laura’s answer) through civilian disaffection, especially of ordinary white women. I often play for my students a clip of Shelby Foote in Ken Burns’ Civil War series in which he suggested that superior Union resources made Union victory inevitable: “I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back. At the same time the war was going on, the Homestead act was being passed, all these marvelous inventions were going on… If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don’t think the South ever had a chance to win that War.” I use this clip to start a discussion about the Confederacy’s rather significant advantages in the war. Given the popularity of the overwhelming resources argument (especially as part of the Lost Cause interpretation), I do think that consideration of internal explanations of Confederate defeat are essential.

Barton Myers: I agree with Susanna. I’ll follow up on a point I mentioned in an early post about internal problems within the Confederacy itself by highlighting one small argument from my new Cambridge book that demonstrates the importance of internal problems in the Confederacy. In my work, I uncovered (mapped) more than one third of the counties in North Carolina that fell into some form of guerrilla warfare by late 1863. This raises the question of what the Confederacy actually was by early 1864 from a geographic perspective. It certainly wasn’t the Confederacy of 1861. The Confederate War Dept., a very understudied entity, was losing command and control at the neighborhood and county level as a result of militant dissent in is many forms from 1861 on. Coupled with Union military occupation this internal resistance of unionists, deserters, and other anti-Confederate elements played an important role in the internal collapse of the Confederacy. Yet, many of these individuals held out ultimate hope of some form of liberation from the Union army, not the success of their own local resistance. A synthesis of both the external (traditional battlefield narrative of victory by the Union Army) and internal defeat arguments (weak Confederate nationalism/chronic violent dissent, etc.) is really necessary to understanding the full picture of defeat. Rooting this synthesis of arguments in the important new work of the digital humanities, mapping projects, military occupation research is one key to understanding why Confederate armies surrendered and why the Confederate government could no longer provide supplies and manpower to those armies at the necessary rate. The battlefield mattered, but seeing the “battlefield” as only the symmetrical, conventional fields of Gettysburg and Vicksburg doesn’t explain the entire war’s end result. Only a broader definition of battlefield, which includes the world of military occupation and militant resistance on the “home front” does that.

Laura Edwards: I had a hard time thinking about this question, because there are so many ways to answer it. I really liked Kathleen’s comment about how the Civil War really solidified a region, “the South,” and the regional identity of “southerners.” That identity has had profound political implications, usually associated with racism and opposition to progressive change. Yet, as Bob also pointed out, using the example of William Faulkner, regionalism has enriched American culture as well. For better or worse, “the South” is now part of the America that was unified during the Civil War.

That said, I was also trumped by this question because it presumes an outcome of the war that was not actually accomplished at the time and never was a foregone conclusion: the extension of rights to minorities and, presumably, all Americans. Although I understand the larger point, the phrasing is illustrative of many historians’ tendency to credit the Reconstruction Amendments with doing things that, in law, they did not really do. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, but did not extend civil, let alone political rights to former slaves or anyone else. Neither did the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments, although they did enhance the ability of individuals to claim civil and political rights. Both amendments gave the federal government oversight to ensure that states would not deny rights on the basis of race. But neither established a national standard of rights that all Americans could claim, despite the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “privileges and immunities” to all American citizens.

The Reconstruction Amendments and related legislation left the power to define and grant civil and political rights with the states. States also retained the power to regulate for the public welfare, powers that they traditionally used broadly in ways that limited the rights of individuals. States, for instance, had always determined which individuals claim civil and political rights, and most states excluded the vast majority of the population from some, if not all those rights—not just racial minorities, but also women and many propertyless white men. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments did not extend protections to these other groups who had experienced discrimination on the state level. Civil rights, moreover, were limited primarily to the possession and transfer of property and access to the courts. While important, they did not—and could not—address the array of structural problems with which many Americans, particularly former slaves, struggled. States had Bills of Rights in their state constitutions, but those rights were less absolute than we tend to think today, because they were always balanced against the public good. To complicate matters, the federal government did not build the kind of bureaucratic infrastructure necessary for enforcement within states, and the federal courts then hamstrung enforcement efforts. States’ denial of rights thus continued after the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, as they found new ways to limit both the meaning and accessibility of civil and political rights. Only recently could women claim the full array of civil rights as men. And it was not just states of the former Confederacy that found ways to use their traditional regulatory powers to deny rights to racial minorities. It took concerted political effort, over the next century, to make the ideal of civil and political equality for all American citizens a reality. Even then, America still struggles to square its promises with its reality.

That situation is much more complicated than the question suggests. It took far longer for those denied rights—not just racial minorities, but all Americans—to obtain them. It also took far longer for rights to take on the form that they have today, as powerful claims that individuals can make to mobilize state and federal authority on their behalf. But that is also an unintended outcome of the Civil War—a rights revolution, which opened up new expectations about individuals’ claims on government.

Latest Comments

Have your say!