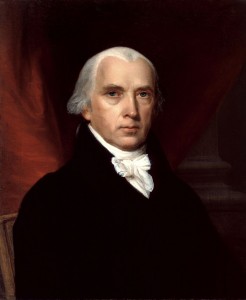

Niccolò Machiavelli and James Madison seem to have little in common. In the popular imagination Machiavelli, despite decades of scholarly effort to rehabilitate him as a civic republican, retains his dark glamour as the author of The Prince, the theorist of power politics, of a realm beyond conventional morality where it is better to be feared than loved. Ironically, his nefarious reputation has assured him a measure of immortality. Madison, by contrast, is the father of the American Constitution, the bright child of the Enlightenment, inheritor of Locke, Montesquieu, and Hume, who brilliantly devised the architecture that would link the thirteen states into a more perfect union.

Niccolò Machiavelli and James Madison seem to have little in common. In the popular imagination Machiavelli, despite decades of scholarly effort to rehabilitate him as a civic republican, retains his dark glamour as the author of The Prince, the theorist of power politics, of a realm beyond conventional morality where it is better to be feared than loved. Ironically, his nefarious reputation has assured him a measure of immortality. Madison, by contrast, is the father of the American Constitution, the bright child of the Enlightenment, inheritor of Locke, Montesquieu, and Hume, who brilliantly devised the architecture that would link the thirteen states into a more perfect union.

The chasm separating Machiavelli from Madison, a chasm of time, modes of thought, and values, diminished after the publication of J.G.A. Pocock’s The Machiavellian Moment, which linked the two political theorists through a shared civic republican tradition of discourse and thought about politics centered around virtue and corruption. Yet, in many ways Madison and “the Federalist persuasion,” (to use Gordon Wood’s term) bid that old civic republican world adieu.

Nevertheless, there is a deeper affinity between the two and it lies not in who influenced whom, but in viewing both theorists as pragmatists, visionaries, and committed republicans seeking to solve the same problem, that of renovating and modernizing republican governments. If we ask a new question, might it be that Machiavelli anticipated Madison in some ways? We see things in a new light.

Why is the experiment of the extended republic to be rejected merely because it may comprise what is new?

Let us recall Madison’s dilemma, in his own words, “Why is the experiment of the extended republic to be rejected merely because it may comprise what is new?” Conventional wisdom decreed that republicanism (government by the people, as a shorthand) required the face-to-face polity. When republics expanded territorially, they did so by way of leagues with the Articles of Confederation a prime example. Was it even possible to extend the concepts and institutions of popular government to large states asked the American framers? History and theory were in agreement, constructing an extended republic was as futile as trying to square the circle.

Madison’s counterintuitive answer in Federalist 10 was a turning point in the history of political thought. Popular governments were stronger and more enduring when larger in size. The specific solution is familiar: a compound union resting on electoral representation and federalism that enabled popular government to take on renewed life in the modern era. Machiavelli had his own “Madisonian Impulse” and deserves to be recognized as the first modern political theorist to envision the possibility of a republic with a large population extending over a broad territory.

The sixteenth century was a dark time for republics. Republican government, the tradition of conducting government by means of dialogue, was increasingly dismissed as quaint and outmoded. The new era of princes in command of mass armies made the small size of and collective decision making of municipal republicanism seem a tradition that had outlived its relevance. The institutions and concepts of republicanism had developed inside the walls of cities, in small face-to-face communes. It was not at all clear how those institutions and concepts could be altered to encompass a larger territory and population.

The sixteenth century was a dark time for republics. Republican government, the tradition of conducting government by means of dialogue, was increasingly dismissed as quaint and outmoded. The new era of princes in command of mass armies made the small size of and collective decision making of municipal republicanism seem a tradition that had outlived its relevance. The institutions and concepts of republicanism had developed inside the walls of cities, in small face-to-face communes. It was not at all clear how those institutions and concepts could be altered to encompass a larger territory and population.

Machiavelli grasped that how to enlarge the republic was the problem, practical and theoretical, of the hour and the age. He conceived of a daunting project, grounded in ancient learning and modern politics, to remedy the Italian situation and modernize republics for the brave new world of territorial monarchies on the move. Machiavelli intended his The Prince and the Discourses on Livy “to work the good” as manifestos that would inspire and guide the founding of an unprecedented republic for a new political era.

Reading The Prince and the Discourses on Livy in light of scholarship on early modern state formation, the history of popular movements, archival documents from Leo X’s pontificate and Florentine history, draws our attention to a critical period in the history of republican thought and illuminates its adaptation to the most consequential changes in the landscape of the modern state. Walk with Machiavelli through his ancient Rome and witness an exceptional political imagination roaming beyond the boundaries of the city-state world that shaped and constricted the imagination of contemporaries. The goal is to renovate the institutions of that great territorial republic, ancient Rome, in order to found a new kind of republic, one not only territorially expansive but providing a voice for the people. In particular, we should analyze the Discourses as Machiavelli’s effort to solve the three problems faced by an extended republic: how to expand in space, how to survive in times of war and peace, and how to graft participatory politics onto an extended territory.

It is fair to ask if, however intriguing, this foray into the history of political thought speaks to contemporary dilemmas. At this time, when the old verities of the post-war world are being devoured by globalization, rising economic inequality, terrorism, and attendant military actions we seem to have entered into an era of unprecedented challenges. Moreover, the future of liberal democracy or “extended republics” in an era dominated by global capital, economic forces, failed states and non-state actors seems tenuous at best. It may help to remember that there have been other ages that likewise lent themselves more to brooding than to hope, when popular government seemed a quaint anachronism and the future boded either domination by the powerful or descent into violence. Machiavelli wrote during just such an era. The path forward is not immediately apparent, but someone may be toiling in obscurity to devise a remedy and it may take decades, even centuries of turmoil, discussion and debate, innovation in theory and practice, to reach a provisional solution. Just as there was a “Machiavellian Moment” and later a “Madisonian Moment” we may well be living through another critical juncture, when all accumulated wisdom seems inadequate to the task. Rest assured, there will be a breakthrough, though we may have a long time to wait.

Latest Comments

Have your say!