Image credit: AP

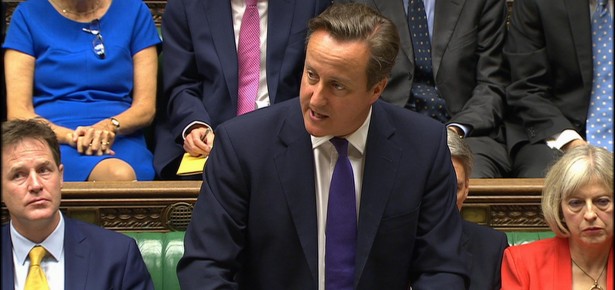

On September 26th 2014, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom’s parliament debated and voted on the government’s motion on air strikes in Iraq against ISIL. The government won with 524 to 43 – a majority of 481 – in favour. A key part of the government’s motion was the ‘request of the government of Iraq for international support to defend itself against the threat ISIL poses to Iraq and its citizens, and the clear legal basis that this provides for action in Iraq’. In this post, I identify and query the consent of the government of Iraq operating, in the parliamentary debate on the motion, as a shortcut around broader issues of international legality and popular support within Iraq.

One shortcut role for the consent was in relation to the broader issues of international legality. International legality was especially important in light of the problems surrounding the international legal basis for the last intervention into Iraq and the more recent vote on intervention in Syria (without a clear consensual basis) which did not achieve a majority in favour. Consider the contribution of the Conservative MP Clark: ‘[t]he legal case for intervention in Iraq is clear with its Government’s inviting us’, or the Liberal Democrat Campbell, ‘[t]his is not, however, 2003. It is an entirely different set of circumstances, an important feature of which is the fact that we would be responding to a request made by the lawful Government of [Iraq]’. The repeated stress on the clarity of the international legal basis provided by the consent of the government of Iraq strengthened the message that there was a sufficient legal basis, which can help to explain why broader issues of legality – such as potential bases to query the validity of the consent, the question of what would happen if the consent was to be withdrawn or the prospects of a UN Security Council chapter VII resolution – were overlooked.

Another shortcut role for the consent of the government of Iraq concerns the level of general support amongst the population of Iraq for the intervention. The level of support was particularly relevant given the doubts that surrounded the degree to which the UK forces were welcome during the last intervention in Iraq, which raised major ethical and effectiveness issues. This shortcut role was not so explicit in the debate, but can be linked with certain comments. For instance, Democratic Unionist Party MP Dodd’s description: ‘[t]he sovereign nation of Iraq faces a perilous time and it has submitted a request for assistance at this crucial juncture, to assist it in protecting its national security, and the security and safety of its people’. Through assimilating the nation of Iraq into the consent of the government, such comments serve to project a general sense of welcome from the Iraqi state including the population. This, in turn, can help to explain why the parliamentary debate largely left to one side broader issues of popular support; one exception being Conservative MP Baron’s position that: ‘[t]here is no point in military intervention if the politics are not right—and they are not. Many of those who served under al-Maliki are still in place, and many Sunnis still feel alienated. Without the hearts and minds policy being right, military intervention will not be enduring.’

If consent served as a shortcut in the UK political debate on the broader issues of international legality and popular support surrounding the air strikes in Iraq, it is reasonable to imagine that it could serve a similar role in future debates on military action both in the UK and elsewhere. This makes it useful to consider more carefully what valid consent to military intervention signifies both in terms of international legality but also the support of the host population. These are issues that are addressed in the course of my recent book: Popular Governance of Post-Conflict Reconstruction: The Role of International Law (CUP 2014).

In the book, I focus on case studies of more comprehensive international engagement in Sierra Leone and Afghanistan, but the analysis provides insights that are of relevance when thinking about parliamentary debates on military intervention. Of particular note for the parliamentary debate on air strikes in Iraq is the insight that when there has been a military component to an international engagement post-conflict, the consent of the host government has tended to be supplemented with a UN Security Council chapter VII authorization. One reason for this is that the independent legal basis, found in a chapter VII authorization, serves to reduce the dependency of the ongoing military involvement on the preferences or identify of the domestic government. Another useful insight is that although the government acts in the name of the state and its people, exercising both the sovereign rights of the state and the right of the people to self-determination, this should not be equated with a meaningful claim to be an embodiment of the will of the people. This is because governmental status in international law can rest on little more than recognition of status from the same international actors that keep the government in authority.

In sum, the recent parliamentary vote on UK involvement in airstrikes against ISIL in Iraq highlights that consent can be a shortcut around broader issues of international legality and popular support in political debates on military intervention. In both respects, though, consent has some limitations, including that it can readily be withdrawn and stems from the government not the general population. Such limitations are not necessarily a reason to be dissatisfied with the current condition of international law, but should be kept in mind by parliamentarians, as they provide a basis for making fuller use of the opportunity that they are afforded to scrutinize and influence the approach of the UK government to military deployment. This is an aspect of foreign policy for which the support of both the UK population and the host population can be vital, but recent history demonstrates can too readily be taken for granted.

Latest Comments

Have your say!