There is no way to improve on Dracula.

There is no way to improve on Dracula.

The poster for the new Dracula film features a battle-worn hero/archangel fighting for his family. Young, good-looking, buff, he’s probably a bore (all the beautiful young people on The Vampire Diaries are boring, even to look at). But the poster does provide a glimmer of original gothic in Dracula’s Rorshach wings become crackling, autumnal leaves then degrading into ravens, then bats flailing through the sky.

I’ll take my Dracula pure. There is a frisson in reading Stoker’s Dracula when Harker remembers seeing “the Count’s head coming out from the window” and then “saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over the dreadful abyss, face down with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings.” As Harker slowly realizes, “it could be no delusion. I saw the fingers and toes grasp the corners of the stones, worn clear of the mortar by the stress of years, and by thus using every projection and inequality move downwards with considerable speed, just as a lizard moves along a wall” (chap 4).

In the following clip, Frank Langella enacts this estranging being—prehensile fingers slither his reptilian body down, down a fortress wall, fingers like claws straining with sexual aggression as they claw through the glass window, and his upside down vampiric face freezes fear and longing into the vulnerable Lucy.

I was trying to understand this frisson in my book From Dickens to Dracula: Economics, Gothic, and Victorian Fiction. As a professor for 25 years, I’ve taught the gothic novel many times, realizing that it is not just a cream puff genre to be read only for entertaintment, although it does provide that. With each new reading of Dracula, I have come to agree with James Kincaid’s statement that “If the gothic can be explained, it is no longer gothic,” a statement that points up “the decentering at the heart of the gothic.”58 Like the art works by eighteenth-century painters Piranesi and Fuseli, the gothic, which reaches its full-blown height circa the French Revolution (nothing more gothic than the guillotine or a mad King George III) captures what is now called “edgy” in film circles.

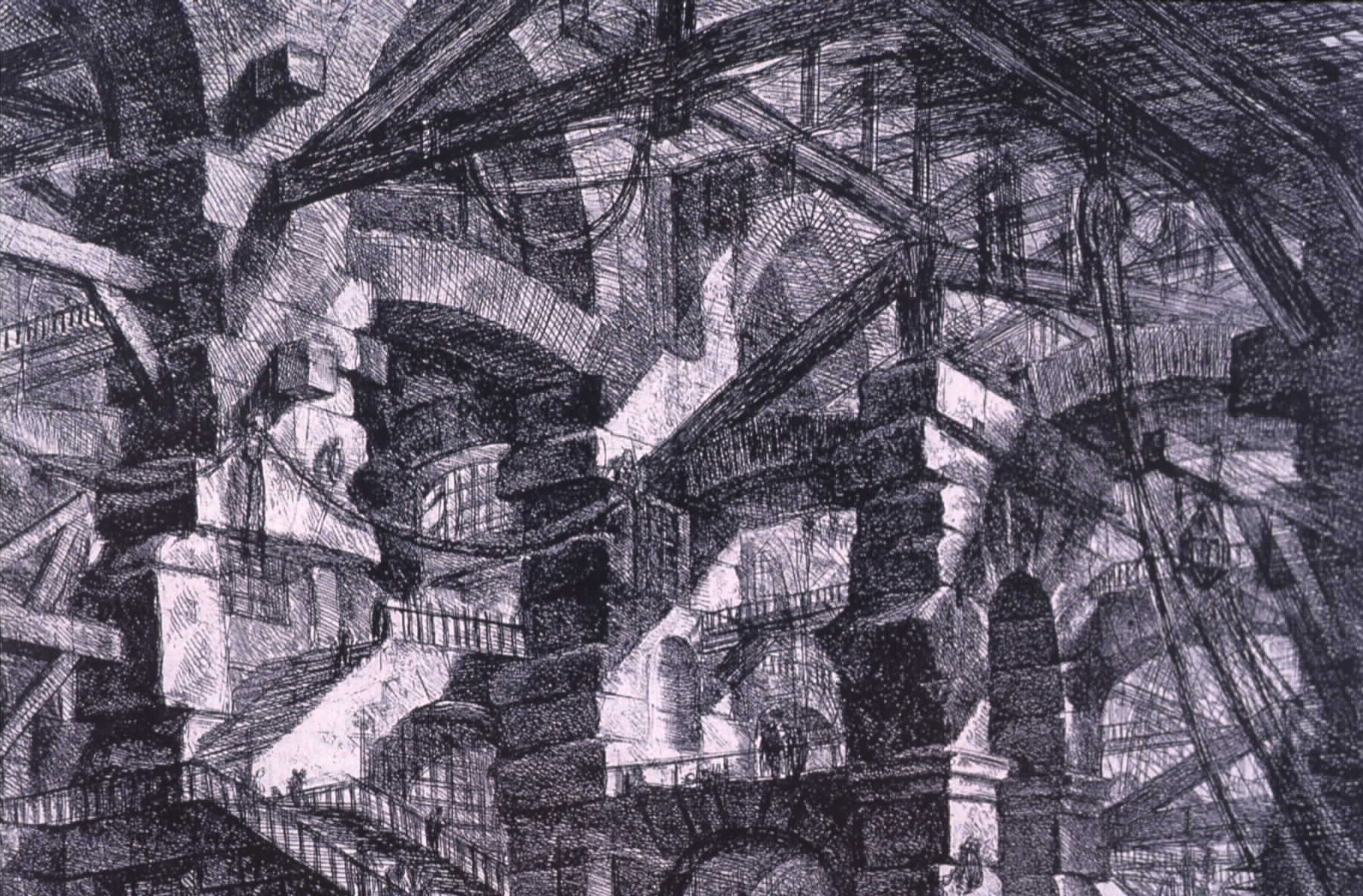

The “Carceri” (Prison) created by Piranesi in 1745 (see left) is a bizarre Gordian Knot of bridges, stairways, keystones, and ropes brilliantly illustrating the architecture of modernity with its futility and meaninglessness. Right before the modern state establishes vast bureaucracies, Piranesi features monolithic societal structures that imprison us; we sense in them what we cannot fully explain—confronting insanity, evil, and senseless amorality, the gothic affords these states of mind to us subliminally and teases us with the realization that the dark side is right there where we were trying to hide it, in ourselves.

The “Carceri” (Prison) created by Piranesi in 1745 (see left) is a bizarre Gordian Knot of bridges, stairways, keystones, and ropes brilliantly illustrating the architecture of modernity with its futility and meaninglessness. Right before the modern state establishes vast bureaucracies, Piranesi features monolithic societal structures that imprison us; we sense in them what we cannot fully explain—confronting insanity, evil, and senseless amorality, the gothic affords these states of mind to us subliminally and teases us with the realization that the dark side is right there where we were trying to hide it, in ourselves.

As I note in my book, the gothic might illustrate the “‘disembodied, ghostly articulations within and against the dream of full, simple, self-evident’ and ‘stable’ speech that is the marker of realist fiction.59” Against realism’s safe, rational narrative, gothic writers throw a gauntlet of terror in Frankenstein (1818), The Italian (1797?), and The Monk (1796). In doing so, these gothic novels remind us that realism is nothing of the kind if it does not include the dark side of reality.

Like Piranesi’s work, Fuseli’s 1781 “Nightmare” (right) captures the edginess of the gothic: note the unnerving blank stare of the agitated horse, the utterly vulnerable, sexually available woman—the succubus whose stare eerily follows the viewer and whose shadow on the red curtain behind him depicts the outline of a bloated Satan. We do not need to know what the painting means—its undulating lines and curtains upon curtains (concealing what?) are already imprinted on our psyches.

Like Piranesi’s work, Fuseli’s 1781 “Nightmare” (right) captures the edginess of the gothic: note the unnerving blank stare of the agitated horse, the utterly vulnerable, sexually available woman—the succubus whose stare eerily follows the viewer and whose shadow on the red curtain behind him depicts the outline of a bloated Satan. We do not need to know what the painting means—its undulating lines and curtains upon curtains (concealing what?) are already imprinted on our psyches.

In From Dickens to Dracula, I note Julian Wolfreys’s insight that after 1820 the gothic revealed itself in glimpses; instead of being a genre, the gothic becomes a “haunting spirit” that appears in “phantom fragment[s]” in other genres.56 I point out that these phantom fragments appear in discriptions of Victorian banking panics, in Marx’s gothic images of capitalism, and in one Victorian economist’s (Walter Bagehot) love letters to his fiancée—showing that modern capitalism can only be described in gothic language: if we didn’t know that, we learned once again in the 2008 doppelganger of the crash of 1929. I go on to analyze Dracula or The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (expected) but also how gothic glimpses appear in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and Dickens’s very realist Little Dorrit (that features a Piranesi-like debtor’s prison that captures all who enter, prisoner and visitor alike). Yes, there is no way to improve on Dracula or the gothic, either in its full-blown eighteenth-century form or the gothic glimpses that appear in so many other genres and impel popular culture even today. It’s telling us something.

Latest Comments

Have your say!