The shelling of the Belgian village of Dickebusch in April 1916 was hardly unexpected. Well within range of German guns when the mobile operations of summer and fall 1914 had given way to the trenches of 1915, its destruction was, if anything, overdue.

While most of the inhabitants voluntarily evacuated, the remainder were compelled to do so by order of the Belgian military on 14 May 1916. Though the reaction of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which held the line in the vicinity, is not recorded, it is safe to conclude that they were not unduly dismayed, since the proximity of the inhabitants, it was thought, compromised security, complicated logistics and adversely affected the troops’ discipline and health – affected, in other words, the smooth operation of the military machine. They were, in Clausewitzian terms, friction.

If for no other reason than that local people ran shops, sold beer and wine, and were reminders of the civilian life they had left behind, not to mention just what they believed themselves to be fighting for, the troops themselves probably had mixed feelings about Dickebusch’s demise. On the other hand, they took to wrecked villages like vultures to carrion, picking over building materials and household contents, just about anything that would make trench and billet a little more comfortable. Only days later it is no surprise, then, that an inhabitant armed with a pass stumbled across a group of 28th Canadian Infantry Battalion men huddled around an officer. Obscured by the gas mask that he had donned specifically for the purpose, the officer was harvesting honey from the inhabitant’s hives – the crime at Dickebusch.

Categorizing the incident at Dickebusch as a crime may seem overly dramatic, but that is exactly what it was, war or no war. On 26 May 1916, Major Arthur Murray Jarvis, Assistant Provost Marshal, 2nd Canadian Division, recorded the receipt of a claim for 175 francs for loss of honey and damage to an evacuee’s beehives. In charge of divisional policing, Jarvis took his duties, including the nightly writing up of the unit war diary in which the details of this western front snapshot are recorded, very seriously indeed. Though the British were willing to compensate inhabitants whose property had been accidentally damaged by the troops, they were not prepared to do so in instances of wilful damage or theft, which this most certainly was and which were considered disciplinary issues.

As the infantry were regularly rotated between front and rear, the investigation of the crime at Dickebusch, or any crime involving combat troops, was no straightforward undertaking. Though the 28th had returned to the trenches since the claim’s receipt, when it was next relieved the 6th Brigade appealed to the accused officer to step forward of his own accord.

While an identification parade of all 28th Battalion officers was slated for 8 June, the war intervened, with two companies of the 28th all but wiped out by the detonation of four German mines. During subsequent counterattacks to recapture what became known as the Hooge craters, part of the larger action known as the Battle of Mount Sorrel, 2–14 June 1916, the battalion’s two remaining companies sustained heavy casualties. At least part of the explanation for the derailment of Jarvis’s investigation can be attributed to the fact that it was a near certainty that the suspects were among the 700 casualties sustained by the 28th at Sorrel. While Jarvis had come to the conclusion that the ringleader was a Lt Murphy, since killed at Hooge, as days became weeks and as other matters demanded attention, the sad affair of the ‘honey-loving’ officer was quietly, it seemed, laid to rest.

When the Canadian Corps suddenly insisted that matters be ‘cleared up at once’ at the end of June 1916, Jarvis appealed to the 28th to settle the claim out of regimental funds. Though the unit initially agreed to do so, more obstruction and flip-flopping ensued. For reasons not altogether clear, the unit eventually disavowed any responsibility whatsoever, instead pinning the blame on a lone survivor, a Pte Dennis, from whom it had obtained a confession.

With a move to the Somme looming, Jarvis concluded that the case had ‘died a natural death’, at least, that is, until 5 August 1916 when the 28th Battalion offered a token payment of 50 francs, which a Belgian official thought ‘derisive’ and rejected out of hand. With national sensibilities at stake, the affair was taken out of Jarvis’s hands once and for all. ‘The theft of honey case appears to be drawing to a close’, his final entry on the matter reads. ‘The G.O.C. has asked for a resumé of the whole proceedings & will adjudicate upon the matter finally.’

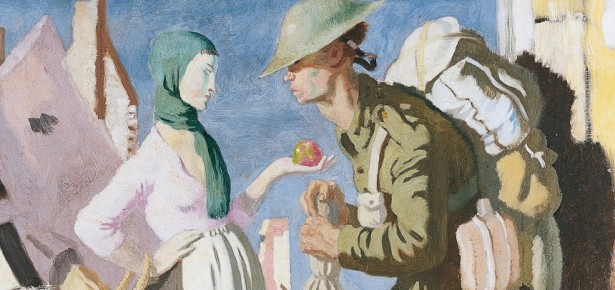

Unfortunately just how or even if the matter was ultimately resolved shall likely remain a mystery. The only narrative on the subject that has been uncovered – Jarvis’s – ends. That the crime at Dickebusch bears an uncanny resemblance to Ralph Hale Mottram’s Crime at Vanderlynden’s, in which a fictional claims officer, Lt Dormer, fruitlessly and absurdly chases the ‘469 Trench Mortar Battery’ across Flanders in an attempt to fix blame for the desecration of the local shrine in ‘Hondebecq’, this is perhaps only fitting.

Art, it seems, does imitate life.

To read the full excerpt, click here.

Latest Comments

Have your say!