Ask philosophers of the present why they read philosophers of the past, and the chances are they will say: to tap into new ways of exploring the questions that philosophy is currently trying to answer. As present-day philosophy values clarity and strength of argument, this usually shapes both who present-day philosophers consider worth reading and how they go about reading them.

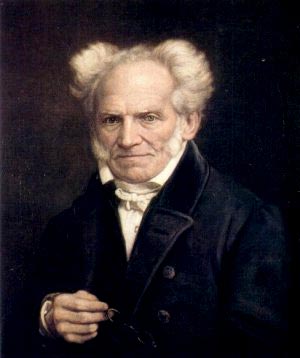

Arthur Schopenhauer

It is not an approach that has worked to the favour of Arthur Schopenhauer, the German post-Kantian philosopher known for his flamboyant metaphysics and his message of pessimism. Since the earliest reception of his philosophy, Schopenhauer has often been thought of as a writer whose remarkable literary gifts have not been matched by his powers of rational persuasion. A prominent contemporary philosopher once invited us to regard Schopenhauer’s grand-style metaphysical picture of the world—the world, Schopenhauer claimed, is nothing but a blind will that pulses in all existents—as a “work of the creative imagination.” Yet philosophers want to be known not for their imagination, but for the power and clarity of their reason, and indeed for their success in uncovering the truth. And metaphysics to the side, how do you argue against pessimism anyway? Schopenhauer’s pessimism is often taken as the hallmark of his philosophy and the main basis of his title to philosophical fame, but it would seem to be the element of his philosophy least open to reason-giving. We don’t normally expect that optimism or pessimism can be budged by argument (though if they can, you’re more likely to argue a person into pessimism than out of it!).

Imagination, of course, does have a role to play in philosophy, even in the forms most staunchly devoted to the primacy of argument. (Think of the sheer power of the imagination displayed in modern-day thought experiments that test one philosophical theory or another). But to work off the hypnotic hold which the notion of “reasons” and “arguments” has on the way we approach philosophers, we need to begin thinking more broadly about the different ways in which the notion of philosophical truth may be understood, or about the different ways in which philosophies can “speak” to us.

The way philosophy speaks to us is often irredeemably subjective, its ability to address us depending on highly individual journeys of emotional and intellectual formation.

The way philosophy speaks to us, of course, is often irredeemably subjective, its ability to address us depending on highly individual journeys of emotional and intellectual formation. Similarly, there are some ways in which philosophy “speaks” that may seem irrelevant to philosophical inquiry. Philosophies are the works of specific individuals with particular life trajectories and particular temperaments, and thus may sometimes “speak” to us about their author in more personal or biographical ways. In this sense, it has sometimes been said that we can see more than a trace of Schopenhauer-the-man—of his gloominess, his anxious disposition—in the pessimistic philosophy he left behind. But of course individuals rarely come to philosophy as sheer individuals; often (if not indeed always), what they write about and how they write reflect larger concerns that make them “speak” for their time. Plato’s Phaedrus could not have been written in 21st-century Europe, just as Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus could not have been written in 4th-century BC Athens.

Something similar could be said about Schopenhauer and his main work, The World as Will and Representation. Schopenhauer, it has sometimes been said, “speaks” to us as someone expressing the spiritual homelessness that resulted from the process of secularisation, as the cosmos was gradually sanitised of its gods. His ruthless vision of the world is the vision of the kind of people we have become: people with no room for romantic fairy-tales about an orderly world governed by a benevolent deity who made sure to outfit it as the best of all possible worlds. In a word: disenchanted people devoid of wonder.

So where does this leave us, one may ask, when it comes to engaging Schopenhauer? “Engagement” is a funny and rather shapeless word that verges on being a term of art, signifying the kind of concern only professional philosophers would be likely to have. To decide how to “engage” a philosopher is to decide how to write one’s next article or book on him. But arguments about how a philosopher should or shouldn’t be read aren’t as inert or cosmetic or “academic” as that. A book about how to read a certain philosopher (certainly my book as I tried to write it) is a way of adjusting the light in which one reads a philosopher, of tuning oneself to elements of the writing that were there but perhaps passed unnoticed. Once noticed, they allow one to experience the work in a new way (or help clarify the way one has already been experiencing it). Interpretations create new experiences. And philosophical experiences feed into our experience of the world.

In the case of Schopenhauer, this is something I have tried to do in my book by bringing into focus the importance of the visionary elements of his philosophy, and connecting them to an aesthetic experience that defined 19th-century aesthetic sensibility—the experience of the sublime. From there, it is another journey to trace the roots of these visionary elements in ancient philosophy; and another journey to meditate on what this means for us—for us as readers to whom Schopenhauer “speaks” by ventriloquizing a wider experience of the wonderless world. Can wonder that has been lost ever be regained? If it even leads us to raise this question at all, pessimism is clearly more of a help than a harm.

Latest Comments

Have your say!