Pita Kelekna

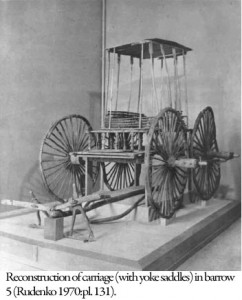

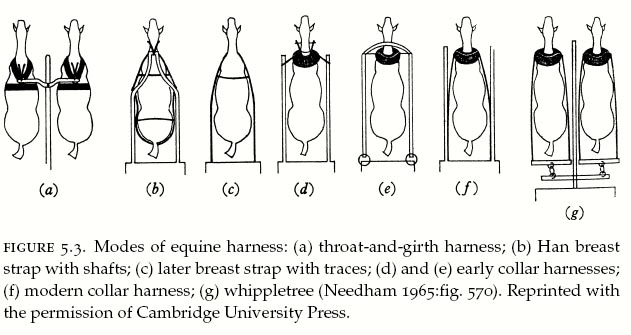

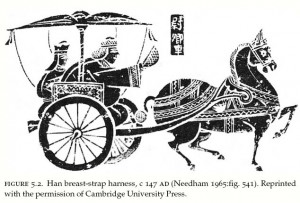

In the fourth millennium BC, yoke harnessing was originally designed for paired bovid draft. Also known as throat-and-girth, this mode of harnessing was anatomically inappropriate for equids and did not efficiently exploit the full tractive force of the horse, necessarily utilizing yoke-saddles to alleviate pressure on the trachea. Nevertheless it long persisted in the West. Because this archaic system of harnessing had proven entirely inadequate in transporting wheat even short distances from the Italian latifundia to the capital, Imperial Rome had been compelled to rely on grain shipments from North Africa and Sicily in order to feed its populace. Yet in the Far East, the Chinese achieved two significant breakthroughs during the first millennium BC, inventing first the trace harness (breast strap) and then the even more efficient contoured collar harness. Both devices bore principally on the sternum of the horse, linking the line of traction directly to the skeletal system. Thus, while Roman chariots of minimal size, accommodating two persons at most, were often drawn by four horses, contemporary Han vehicles with heavy upcurving roofs, frequently carrying six passengers, were usually drawn by a single horse. Trace and collar harnesses greatly increased agricultural productivity in China. Unfortunately, nearly a thousand years would elapse before these great innovations diffused westward across Eurasia to have a comparably beneficial effect on medieval Europe.

In the fourth millennium BC, yoke harnessing was originally designed for paired bovid draft. Also known as throat-and-girth, this mode of harnessing was anatomically inappropriate for equids and did not efficiently exploit the full tractive force of the horse, necessarily utilizing yoke-saddles to alleviate pressure on the trachea. Nevertheless it long persisted in the West. Because this archaic system of harnessing had proven entirely inadequate in transporting wheat even short distances from the Italian latifundia to the capital, Imperial Rome had been compelled to rely on grain shipments from North Africa and Sicily in order to feed its populace. Yet in the Far East, the Chinese achieved two significant breakthroughs during the first millennium BC, inventing first the trace harness (breast strap) and then the even more efficient contoured collar harness. Both devices bore principally on the sternum of the horse, linking the line of traction directly to the skeletal system. Thus, while Roman chariots of minimal size, accommodating two persons at most, were often drawn by four horses, contemporary Han vehicles with heavy upcurving roofs, frequently carrying six passengers, were usually drawn by a single horse. Trace and collar harnesses greatly increased agricultural productivity in China. Unfortunately, nearly a thousand years would elapse before these great innovations diffused westward across Eurasia to have a comparably beneficial effect on medieval Europe.

With superior Chinese harnessing methods, the higher speed and stamina of the horse over the ox (50 per cent more meter-kilograms per second in traction) were critically important in the inclement weather of northern Europe, where often the very success of a crop depended on plowing, planting, or harvesting within a narrow timeframe of favorable conditions. Deployment of the horse in agriculture necessarily had social repercussions. Earlier with the slow ox, farmers had been obliged to live dispersed in tiny hamlets alongside their fields. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, however, peasants began to aggregate in larger villages and towns, the faster equine draft allowing them to easily haul the plough to their fields each day, also to reach outlying areas not previously cultivated. Horse draft additionally served as a catalyst in the development of intensive mixed farming, permitting greater regional specialization in the pastoral sector, with emphasis on cattle-rearing for meat and dairy, also on sheep-rearing for wool.

fields each day, also to reach outlying areas not previously cultivated. Horse draft additionally served as a catalyst in the development of intensive mixed farming, permitting greater regional specialization in the pastoral sector, with emphasis on cattle-rearing for meat and dairy, also on sheep-rearing for wool.

Nonetheless, it is held that by far the greatest benefit achieved in the transition from ox- to horse-draft was in the sphere of transportation. By the end of the thirteenth century, horses were responsible for over 75 percent of haulage, featuring prominently in urban communities and producing a marked effect on the economy. Velocity of transit not only sped goods to market, it also facilitated rapid circulation of heavy gold and silver coins in a progressive economy. Whereas earlier, transport had been primarily along coastlines, rivers, and inland canals, beset in winter by gales and ice, now rural regions away from navigable waters flourished as horse haulage overland delivered their products promptly to burgeoning townships and the great fairs of the Middle Ages. Thus, advancing farm techniques and efficient horse transport helped break down the rigid confines of the demesnial system and to lay the foundation for a more flexible economy, eventually freeing European peasantry from its feudal obligations of the past.

In later centuries, as New-World wealth flooded into Europe, highways were generally improved. Different inventions contributed further to transport progress. The movable forecarriage made the maneuvering of four-wheeled wagons more practicable. The “dished” wheel provided greater strength against the sideways thrust, inevitable with the swaying of heavy wagon-loads drawn over uneven surfaces. Soon, hundreds of wagons were entering and leaving European cities each week, many drawn by teams of six or eight horses, transporting loads of up to 6,000 kg. These wagon carrier services were supplemented by gangs of pack horses. Horsepower transported greater loads by vehicle: 305 kg per wagonhorse as opposed to 109 kg per packhorse. But the pack horse was faster and less seriously affected by steep gradients and harsh winter conditions.

The greater speed and reliability of carrier services were so appreciated that an immense variety of goods were transported by road: perishable agricultural products, costly textiles, and imported luxury items. Even in the case of less costly bulk freight along coastal and inland waterways, the beginning and end of journeys often were overland, to and from navigable water. Thus, the two modes of transport were largely complementary; also, horses were employed towing barges along canals. Horsepower additionally helped relocate industries to areas of cheaper labor in remote areas. And in multi-stage production, it transported partial products between local centers of manufacture, thereby intensifying regional specialization and commercial integration.

The stage-coach, distinguished from its wagon-precursor by its leather-strap suspension, later by laminated tensile steel springs, provided the first regularly scheduled passenger services over long distances. Drawn by four to six powerful draft horses, with frequent change of horse-teams en route, the stage-coach was the speediest form of public transportation. Soon too, the stately carriage would be the sumptuary gift exchanged among monarchs. With an efficient transport system and emergent national economy, London grew rapidly to become Europe’s leading port. Braced for the Industrial Revolution, Britain would become the center of a worldwide empire and a developing world economy, as raw materials poured in from overseas, were distributed throughout the provinces, then returned as manufactured goods to the metropolis for consumption or export abroad. And in due course, the multifunctional horse and mule would be exported abroad, to bolster new economies on distant continents.

References:

Needham, Joseph 1965 Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 4. Physics and Physical Technology. Part 2. Mechanical Engineering. With the collaboration of Wang Ling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rudenko, Sergei I. 1970 Frozen Tombs of Siberia: the Pazyryk Burials of Iron-age Horsemen. Translated by M. W. Thompson. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Latest Comments

Have your say!