The 3rd installment of The Horse in Human History blog series

Scythian gold plaque

Traditionally, history focuses upon centralized sedentary civilizations, such as those of Mesopotamia, tending to dismiss nomads as mere barbarians beyond state borders.But how did these intrepid pastoralists successfully traverse the vast hostile expanse of the Eurasian steppes?

First, these migrations were facilitated by the horse.But of tantamount importance were the portable dwellings that enabled mobile herders to survive the climatic extremes of the continental interior.From the Yamnaya horizon, we know that the very first mobile habitation was the covered wagon with hooped canopy.But from later funerary models and pictographs, it seems that a primitive tent was early placed atop the wagon.The initial simple wooden frame, covered by matting or weatherproof felts, probably was easily lifted from the wheels to provide a stable dwelling in camp, while allowing for quick return to mobility as needed.At first conical, then dome-shaped, as the architecture became more sophisticated, the structure was made collapsible for transport by pack animals.Dating from the first millennium BC, even today thousands of trellis tents, known as ger or yurt, continue to dot the steppes.Their collapsible bentwood structure covered by felts allows nomadic horsemen to penetrate the most rugged terrains and to lead their herds to the remotest pastures.

Successive stages in erecting a ger by Mongolian nomads

Conceived as the vitalizing union of male and female, the ger is the nomads’ microcosm of the universe– the dome of its arched roof, the firmament; the smoke hole, the door to heaven.Among nomads, the hearth fire is metaphor for the continuity of clan, family, and herds.On striking camp, a clan grandmother is responsible for transferring the fire coalsto the new encampment and for their division among clan members.

Bentwood technology was utilized for another important item – the spoke-wheeled chariot. The three basic components of this amazing new vehicle were: the box to carry the driver and combatants; an axle and wheel; and a harnessing assemblage. The spoke wheelswere mounted onto the axle between tubular bushings fastened with linchpins. Spokes radiated from a central hub and were mortised in a bent-wood felloe. This required the wood cut to shape be soaked overnight then heated in a vertical structure over the hearth, at which point it was bent by leverage to the correct curvature on a pegged bench.It was then held in shape between stakes on the ground for several days until ready for construction.In harnessing, to adapt the vehicle yoke to horse anatomy, two inverted v-shaped yoke saddles were suspended to fit neatly over the neck of each of the two horses, forward of the withers. The horses were then secured to the yoke saddle by leather straps that ran separately across the neck of the horse and to its mouth to join with the organic or metallic bit.Additional horses could be fastened by traces.

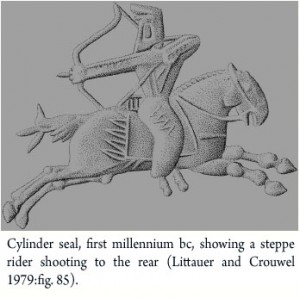

Yet another item requiring wood-bending skills was the horse-archer’s recurved composite bow. A combination of wood, horn, and sinew, this bow was mechanically superior to all others. Tales abound of the steppe equestrian archer’s amazing accuracy at long distance. Stories tell of nomads’ feigning a retreat, only turn and shoot backward at their pursuers over the horse’s tail in the famed“Parthian shot.”These advanced bentwood technologies were not fashioned with stone and flint, but with sophisticated new metal tools. The nomads were accomplished metallurgists, on horseback ever combing the steppes for new mineral deposits and distributing their finished bronze products along complex networks of trade and communication.

accuracy at long distance. Stories tell of nomads’ feigning a retreat, only turn and shoot backward at their pursuers over the horse’s tail in the famed“Parthian shot.”These advanced bentwood technologies were not fashioned with stone and flint, but with sophisticated new metal tools. The nomads were accomplished metallurgists, on horseback ever combing the steppes for new mineral deposits and distributing their finished bronze products along complex networks of trade and communication.

Nor were their talents restricted to the utilitarian. Consummate artists, their ceremonial trappings in silver and gold featured ornamentation in which zoomorphic imagery was paramount: an art form known as “animal style.” Hundreds ofthese precious objects have been retrieved from numerous kurgan tombs scattered across the steppes – huge mounds, underneath which great chieftains lay buried, clad in gold and adorned with precious stones. Spectacular human and animal sacrifice accompanied the funeral, sometimes with hundreds of horses being interred alongside the deceased. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, recounted how Scythian nomads of the steppes escorted the embalmed royal corpse on a hearse from settlement to settlement, ritually slashing their heads and arms in order to lament the death of their king.

Next week: Invasions, Civilizations, and Transcontinental Communication >>

1979 Wheeled Vehicles and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East. Drawings by Jaap Morel. Leiden: Brill

Latest Comments

Have your say!