How horse-borne incursions from the steppes invaded sedentary (agricultural) civilizations, and how horses figuratively shrank the world.

Early horse intrusion into the ancient Near East occurred with the destruction of Akkad toward the end of the third millennium BC. Chiefly kurgan burials were constructed at Alaca Huyuk around this time. By early second millennium BC, Indo-European languages were spoken across Anatolia, the principal being Hittite. The Hittites were preeminent in iron making, an industry over which they exercised strong political control from their fortress at Hattusas. They also placed great emphasis on the war chariot, engaging Kikkuli, a member of the Indo-Aryan-speaking elite ruling the Mitanni Hurrian kingdom of northern Syria, to oversee the disciplined training of their chariot horses. Kikkuli’s strict training-manual details the varied diet and veterinary care provided and how over a seven-month period by alternating gaits, intensifying efforts, and extending distances, the horses were prepared for battle. Deploying a three-man chariot, the Hittites, sacked both Babylon and Aleppo, and in 1286 BC scored a strategic victory over the Egyptians at the Battle of Kadesh, this conflict involving as many as 7,000 war chariots.

Early horse intrusion into the ancient Near East occurred with the destruction of Akkad toward the end of the third millennium BC. Chiefly kurgan burials were constructed at Alaca Huyuk around this time. By early second millennium BC, Indo-European languages were spoken across Anatolia, the principal being Hittite. The Hittites were preeminent in iron making, an industry over which they exercised strong political control from their fortress at Hattusas. They also placed great emphasis on the war chariot, engaging Kikkuli, a member of the Indo-Aryan-speaking elite ruling the Mitanni Hurrian kingdom of northern Syria, to oversee the disciplined training of their chariot horses. Kikkuli’s strict training-manual details the varied diet and veterinary care provided and how over a seven-month period by alternating gaits, intensifying efforts, and extending distances, the horses were prepared for battle. Deploying a three-man chariot, the Hittites, sacked both Babylon and Aleppo, and in 1286 BC scored a strategic victory over the Egyptians at the Battle of Kadesh, this conflict involving as many as 7,000 war chariots.

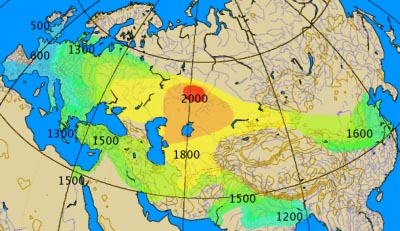

The spread of chariots: 2000BC onward. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported licence.

The Indo-Aryans also made extensive use of the war chariot. These pastoralists from the eastern steppes c 1900 BC began their thousand-year-long migrations southward, sumptuary horse burials marking their route across Bactria, Margiana, and Afghanistan into the subcontinent, where the introduced the chariot, ridden horse, and iron-smelting to India. From the Rgveda, the ten sacred books of Sanskrit hymns, we find that the horse-chariot was believed to control the sun. Its association with celestial bodies and spectacles offers an explanation of cosmic movement. And from martial Indra’s chariot exploits, we learn how Vedic gods aided the invading Aryans in battles over fertile river valleys, again commemorated by elaborate funerary ritual involving horse sacrifice. Because of its antiquity, the Rgveda allows us to trace correspondences with mythical traditions of other Indo-European cultures migrating out of the steppes at this time. The oldest of gods, Sanskrit Dyaus-pitr (Sky Father), appears in early verses and has cognates in Greek Zeus-pater, Latin Ju-piter, and Germanic Tyr. Similarly, the adventures of the Vedic Asvin twins have western parallels in Greek Castor and Polydeuces, Latin Romulus and Remus, and Saxon Hengist and Horsa.

Other Aryans, Iranian-speaking nomads, subsequently migrated south from the steppes along the shores of the Caspian onto the Iranian plateau. These equestrian tribes would elevate horse-riding to a high military art, launching frequent raids against oasis settlements using iron weapons. The Avesta (Iranian holy scriptures) shared much in common with the Rgveda, lauding the heroic feats of champions and kings. But the prophet Zarathustra, who had witnessed brutal acts of violence by nomadic war bands, introduced many religious reforms, moral laws to be applied to the weak and strong alike. His concepts of good and evil, seven days of genesis, last day of judgment, messianic savior, and heaven and hell were to influence many other religions to the west and east.

Iranian militarism culminated in the Achaemenid conquest of sedentary states across the Middle East by Cyrus II, a Zoroastrian who upheld religious freedom throughout his empire. His successor Darius I promoted rapid communication and transport by building thousands of kilometers of roads. He imposed a unitary language and writing system, introduced an imperial legal code, and standardized coinage, weights, and measures across the realm. All of this helped fuse Iranians and other peoples into a unified culture.

Zoroastrian who upheld religious freedom throughout his empire. His successor Darius I promoted rapid communication and transport by building thousands of kilometers of roads. He imposed a unitary language and writing system, introduced an imperial legal code, and standardized coinage, weights, and measures across the realm. All of this helped fuse Iranians and other peoples into a unified culture.

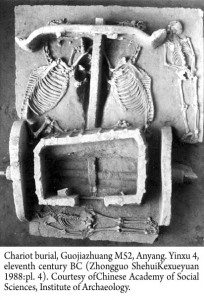

Earlier, it was noted that the chariot had reached China from the west at the end of the second millennium BC; steppe cavalry was adopted in 307 BC, along with archery from the saddle. Also, in steppe fashion, an immense funerary kurgan was constructed by Qin Shi Huangdi in which were interred life-size terracotta figures of 500 horses and 130 battle chariots. During his reign, the Qin emperor instituted economic, legal, and administrative reforms remarkably similar to those of Achaemenids in Persia – even standardizing the axle-length of carts. In fact, at opposite ends of Asia, introduction of advanced horse technologies to these two regions, separated by great distances, triggered almost identical parallel developments. To maintain military readiness, later Han emperors needed to obtain large numbers of steppe horses. This was accomplished by exporting silk and tea westward. Soon, mediated by the nomad, the Silk Road bustled with international trade between Occident and Orient; also western religions diffused eastward.

Buddhism, offshoot of Vedism, traveled northward to China, where, outside Loyang, the White Horse Temple was erected to honor its missionaries. Judaism, Nestorian Christianity, and Islam followed. Horse power had effectively transformed the vast inhospitable wastelands of the Eurasian steppes into an intercontinental corridor of rapid communication. In the sixth century AD, other nomads – Mongol Avars – would speed the important Chinese invention of metal stirrups west to Europe, a factor of critical significance in the later development of medieval knightly warfare. From its nomadic roots, the horse thus facilitated the rise of mighty equestrian empires, opening up Asia, Europe, and North Africa to technological advances and commerce.

Sources: Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) Kaogu Yanjiusuo (Institute of Archaeology) Anyang Gongzuodui (Anyang Archaeological Team):1988 Anyang Guojiazhuang xinan de Yindai chemakeng. Kaogu 10:882–893.

Latest Comments

Have your say!