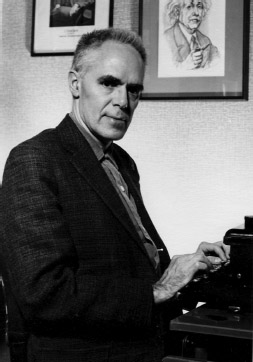

Three years ago, Martin Gardner‘s good friend, MAA Editorial Director Don Albers, interviewed him at length about his childhood, the roots of his fascination with math, and about his career. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be posting the interview in chunks, because his story is absolutely fascinating.

On October 21, Martin Gardner celebrated his ninetieth birthday. For 25 of his 90 years, Gardner wrote the monthly “Mathematical Games” column for Scientific American. His columns have inspired thousands of readers to learn more about the mathematics that he loved to explore and explain. Among his column correspondents were several distinguished mathematicians and scientists, including John Horton Conway, Persi Diaconis, Ron Graham, Douglas Hofstadter, Richard Guy, Don Knuth, Sol Golomb, and Roger Penrose.

On October 21, Martin Gardner celebrated his ninetieth birthday. For 25 of his 90 years, Gardner wrote the monthly “Mathematical Games” column for Scientific American. His columns have inspired thousands of readers to learn more about the mathematics that he loved to explore and explain. Among his column correspondents were several distinguished mathematicians and scientists, including John Horton Conway, Persi Diaconis, Ron Graham, Douglas Hofstadter, Richard Guy, Don Knuth, Sol Golomb, and Roger Penrose.

Gardner’s columns have earned him a place of honor in the mathematical community, which has given him many awards. But he has always declined invitations to accept awards in person, on the grounds that he is not a mathematician. “I’m strictly a journalist,” he insists. “I just write about what other people are doing in the field.” His modesty is admirable, but we insist that he is far more than a journalist. In addition to his massive contributions to mathematics, Gardner has written about magic, philosophy, literature, and pseudoscience.

Over his first ninety years, he has produced more than 60 books, most still in print; many have been bestsellers. His Annotated Alice has sold over a million copies, and the 15 volumes collecting his “Mathematical Games ” columns have gone through several printings (Now beginning a run with Cambridge as a complete set).

Over his first ninety years, he has produced more than 60 books, most still in print; many have been bestsellers. His Annotated Alice has sold over a million copies, and the 15 volumes collecting his “Mathematical Games ” columns have gone through several printings (Now beginning a run with Cambridge as a complete set).

In his ninetieth year, he has returned to Oklahoma, where he was born. He is in good health and full of energy. We look forward to more from him as he begins his second 90 years. What follows is a portion of an interview done at Gardner’s home in Hendersonville, NC in the fall of 1990 and spring of 1991.

DA: In 1914 you were born in Oklahoma. What did your father do?

Gardner: My father was a geologist who owned his own oil company. He was what they called a “wildcatter.” It was a very small company consisting of himself, a secretary, and an accountant. He would go out and look for oil domes. This was before the seismograph. If he found a place that had a prospect of oil, he would hire a drilling company. Most of them were dry holes, but every once in a while he would hit oil.

Gardner: My father was a geologist who owned his own oil company. He was what they called a “wildcatter.” It was a very small company consisting of himself, a secretary, and an accountant. He would go out and look for oil domes. This was before the seismograph. If he found a place that had a prospect of oil, he would hire a drilling company. Most of them were dry holes, but every once in a while he would hit oil.

DA: Does your interest in magic go back to your father?

Gardner: Magic wasn’t a special hobby of his, but he did show me some magic tricks when I was a little boy. I learned my first tricks from him, in particular one with a knife and little pieces of paper on it. I then got aquatinted with a few local magicians in Tulsa, Logan Waite and Wabash Hughes, who worked for the Wabash Railroad.

DA: At what age did this occur?

Gardner: I was a high school student at the time. I’ve never performed magic; it’s just been a hobby. The only time I got paid for doing magic was when I was a student at The University of Chicago; I used to work at the Marshall Field department store during the Christmas season demonstrating Gilbert magic sets. I learned a lot from the experience. That was the first time I realized that you’re really not doing a magic trick well until you’ve done it in front of an audience about a hundred times. Then it becomes second nature, and you know what to say.

DA: What are the elements of a successful magic trick?

Gardner: The most important thing is to startle people, and have them wonder how it’s done. Close-up magic that you do on a table right in front of people is very different from the stage illusions that David Copperfield does. It’s close-up magic that most intrigues me, especially those that have a mathematical flavor. In fact, I’ll show you a little trick here. (He then proceeded to demonstrate a neat topological trick that baffled the interviewer.) In recent years magicians have gotten interested in rubber band tricks that are all topologically based, i.e., they’re violating topological laws. There are entire books published on rubber band magic. (He then demonstrated another trick, and another.) I did a book for Dover Publications on mathematical tricks that has a chapter on topological tricks. I did two massive books for the magic profession: The Encyclopedia of Impromptu Magic and Martin Gardner Presents.

DA: (Looking at the books.) Massive is right.

Gardner: The first book covers tricks that don’t require any special equipment. A lot of them are just jokes and gags of the type ‘bet you can’t do this.’

DA: Your interest in magic is deep.

Gardner: I waste a lot of time on it. Dai Vernon was one of the great inventors of magic. He was a great influence on Persi Diaconis. Persi traveled with Dai for a long time. I knew Vernon very well. I knew Persi when he was a student at CCNY. You probably heard the story how he got into Harvard.

DA: As I recall, he gave you credit for writing a letter of recommendation to Fred Mosteller, the statistician.

Gardner: Mosteller is a magic buff. When Persi said he wanted to get into Harvard, I wrote to Fred and said that Persi can do the best bottom deal and second deal of anybody I know, and that got him into Harvard. I talked to Fred on the phone about it and he said, “Is he willing to major in statistics?” And Persi said sure he’d major in statistics if that would get him into Harvard. So he went up to Harvard, and they had a session together, probably doing card tricks. Mosteller got him into Harvard.

DA: Well, it was a good move on Mosteller’s part. I’m certainly convinced now that your interest in magic is just not a passing fancy.

Gardner: It’s my major hobby. I’ve enjoyed knowing a lot of famous magicians.

DA: What did your mother do?

Gardner: She was a kindergarten teacher before marriage, but then became a housewife, caring for three children. Her hobby was painting, and I have a number of her paintings hanging in the house. Both of my parents lived into their nineties. I had a brother and sister, both younger, who are deceased. I learned to read before I went to school. My mother read the Wizard of Oz to me when I was a little boy, and I looked over her shoulder as she read it. I learned how to read that way. It was very embarrassing when I was in first grade, because the teacher would hold up cards that said ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ and I was always the first to call out the word. She had to tell me to shut up, to give the other children a chance to learn how to read.

Gardner: She was a kindergarten teacher before marriage, but then became a housewife, caring for three children. Her hobby was painting, and I have a number of her paintings hanging in the house. Both of my parents lived into their nineties. I had a brother and sister, both younger, who are deceased. I learned to read before I went to school. My mother read the Wizard of Oz to me when I was a little boy, and I looked over her shoulder as she read it. I learned how to read that way. It was very embarrassing when I was in first grade, because the teacher would hold up cards that said ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ and I was always the first to call out the word. She had to tell me to shut up, to give the other children a chance to learn how to read.

DA: But don’t you think she was doing something to teach you to read?

Gardner: No, she didn’t even know I was learning how to read.

DA: As a kid, do you remember other strong interests in addition to magic?

Gardner: I was very good at math in high school. In fact, it and physics were the only subjects in which I got good grades. I was bored to death by the other classes. I flunked a class in Latin and had to take it over. I just don’t have a good ear for languages.

Gardner: I played a lot of tennis. My father was fairly wealthy, and we had our own tennis court. I also was on the high school tumbling team. I particularly liked the high bar.

DA: Ron Graham is a good tumbler, too.

Gardner: Oh yes! Once I was meeting him for lunch at Bell Labs. A long flight of stairsled to the front door of building. Ron greeted me by walking down the stairs on his hands! He is also an expert juggler and unicycle rider.

DA: You said that you did well in physics, too.

Gardner: Yes. My goal was to go to Caltech. A lot of exciting physicists were there — Millikan for one. But Caltech at that time required two years of liberal arts at a college before transferring. So I went to The University of Chicago intending to transfer to Caltech after two years, but I got hooked on philosophy, mainly to find out what I believed.

DA: Did you encounter the philosopher Rudolph Carnap as an undergraduate?

Gardner: No, he wasn’t there then, but he was there after my four years of service in the Navy during World War II. Using the G.I. Bill, I went back to Chicago and took a course from him in the philosophy of science. I was so impressed by the course that I later persuaded him to do a book on the subject. His wife taped the lectures, and I edited them into a book. Carnap was a big influence on me. He convinced me that questions about metaphysics are meaningless since they cannot be answered empirically or by reason. The essence of Carnap’s philosophy is that an assertion has “cognitive content” only if it can be justified by logic or by empirical testing.

DA: You got your B.A. in 1936, then worked briefly for the Tulsa Tribune as a reporter, and then came back to The University of Chicago to the PR office writing news releases (primarily science releases), and took a graduate course from Carnap. What else did you do until the outbreak of World War II?

Gardner: I had various jobs. I worked as a caseworker for the Chicago Relief Administration, I had to visit 140 families regularly in what was called the Black Belt. I also had several odd jobs: waiter, soda jerk, etc. Remember, this was at the height of the Great Depression.

Latest Comments

Have your say!